Map of Upper Egypt

Map of Upper Egypt

| History of Egypt |

|---|

|

|

|

| Periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt |

|---|

|

All years are BC and AD |

Upper Egypt (Arabic: صعيد مصر Ṣaʿīd Miṣr, shortened to الصعيد, Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [es.sˤe.ˈʕiːd], locally: [es.sˤɑ.ˈʕiːd]) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the Nile River valley south of the delta and the 30th parallel North. It thus starts at Beni Suef and stretches down to Lake Nasser (formed by the Aswan High Dam).[1]

Name

[edit]In ancient Egypt, Upper Egypt was known as tꜣ šmꜣw,[2] literally "the Land of Reeds" or "the Sedgeland", named for the sedges that grow there.[3]

In Arabic, the region is called Sa'id or Sahid, from صعيد meaning "uplands", from the root صعد meaning to go up, ascend, or rise. Inhabitants of Upper Egypt are known as Sa'idis and they generally speak Sa'idi Egyptian Arabic.

In Biblical Hebrew it was known as פַּתְרוֹס Paṯrôs and in Akkadian it was known as Patúrisi.[4] Both names originate from the Egyptian pꜣ-tꜣ-rsj, meaning "the southern land".[5]

Geography

[edit]Upper Egypt is between the Cataracts of the Nile beyond modern-day Aswan, downriver (northward) to the area of El-Ayait,[6] which places modern-day Cairo in Lower Egypt. The northern (downriver) part of Upper Egypt, between Sohag and El-Ayait, is also known as Middle Egypt.

History

[edit]Upper Egypt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital | Thinis | ||||||||

| Common languages | Ancient Egyptian | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• c. 3400 BC | Scorpion I (first) | ||||||||

• c. 3150 BC | Narmer (last) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Egypt | ||||||||

It is believed to have been united by the rulers of the supposed Thinite Confederacy who absorbed their rival city states during the Naqada III period (c. 3200–3000 BC), and its subsequent unification with Lower Egypt ushered in the Early Dynastic period.[7] Upper and Lower Egypt became intertwined in the symbolism of pharaonic sovereignty such as the Pschent double crown.[8] Upper Egypt remained as a historical region even after the classical period.

Predynastic Egypt

[edit]The main city of prehistoric Upper Egypt was Nekhen.[9] The patron deity was the goddess Nekhbet, depicted as a vulture.[10]

By approximately 3600 BC, Neolithic Egyptian societies along the Nile based their culture on the raising of crops and the domestication of animals.[11] Shortly thereafter, Egypt began to grow and increase in complexity.[12] A new and distinctive pottery appeared, related to the Levantine ceramics, and copper implements and ornaments became common.[12] Mesopotamian building techniques became popular, using sun-dried adobe bricks in arches and decorative recessed walls.[12]

These cultural advances paralleled the political unification of towns of the upper Nile River, or Upper Egypt, while the same occurred in the societies of the Nile Delta, or Lower Egypt.[12] This led to warfare between the two new kingdoms.[12] During his reign in Upper Egypt, King Narmer defeated his enemies on the delta and became sole ruler of the two lands of Upper and Lower Egypt,[13] a sovereignty which endured throughout Dynastic Egypt.

Dynastic Egypt

[edit]In royal symbolism, Upper Egypt was represented by the tall White Crown Hedjet, the flowering lotus, and the sedge. Its patron deity, Nekhbet, was depicted by the vulture. After unification, the patron deities of Upper and Lower Egypt were represented together as the Two Ladies, to protect all of the ancient Egyptians, just as the two crowns were combined into a single pharaonic diadem.

For most of Egypt's ancient history, Thebes was the administrative center of Upper Egypt. After its devastation by the Assyrians, the importance of Egypt declined. Under the dynasty of the Ptolemies, Ptolemais Hermiou took over the role of the capital city of Upper Egypt.[14]

Medieval Egypt

[edit]In the eleventh century, large numbers of pastoralists, known as Hilalians, fled Upper Egypt and moved westward into Libya and as far as Tunis.[15] It is believed that degraded grazing conditions in Upper Egypt, associated with the beginning of the Medieval Warm Period, were the root cause of the migration.[16]

20th-century Egypt

[edit]In the twentieth-century Egypt, the title Prince of the Sa'id (meaning Prince of Upper Egypt) was used by the heir apparent to the Egyptian throne.[Note 1]

Although the Kingdom of Egypt was abolished after the Egyptian revolution of 1952, the title continues to be used by Muhammad Ali, Prince of the Sa'id.

Peopling of Upper Egypt

[edit]

In Upper Egypt, the predynastic Badari culture was followed by the Naqada culture (Amratian),[18] being closely related to the Lower Nubian;[19][20][21][22] with some affinities with other northeast African populations,[23] coastal communities from the Maghreb,[24][25] some tropical African groups,[26] and possibly inhabitants of the Middle East.[27]

Mainstream scholars have situated the ethnicity and the origins of predynastic, southern Egypt as a foundational community primarily in northeast Africa which included the Sudan, tropical Africa and the Sahara whilst recognising the population variability that became characteristic of the pharaonic period.[28][29][30][31] Pharaonic Egypt featured a physical gradation across the regional populations, with Upper Egyptians having shared more biological affinities with Sudanese and southernly African populations, whereas Lower Egyptians had closer genetic links with Levantine and Mediterranean populations.[32][33][34]

Position of international scholarship

[edit] Pair of guardian statuettes, depicting Middle Kingdom pharaohs, presumably Senusret I or Amenemhat II, with the white crown of Upper Egypt (left), the other with the red crown of Lower Egypt.[35] The 12th dynasty had origins in Ta-Seti, Upper Egypt.[36][37]

Pair of guardian statuettes, depicting Middle Kingdom pharaohs, presumably Senusret I or Amenemhat II, with the white crown of Upper Egypt (left), the other with the red crown of Lower Egypt.[35] The 12th dynasty had origins in Ta-Seti, Upper Egypt.[36][37]

In the view of Egyptian scholar and editor of UNESCO General History of Africa Volume II (1981), Gamal Mokhtar, Upper Egypt and Nubia held "similar ethnic composition" with comparable material culture.[38] Mokhtar described a notable difference between the communities with Upper Egyptians having adopted a system of writing earlier due to the exigencies of the Nile Valley whilst their Nubian counterparts were more reticent due to their higher reliance on mobile, stock-raising as an expressed feature of their economy.[39]

UNESCO International Scientific Committee Chair for GHA and archaeologist, Augustin Holl, stated that Egypt was situated in an intersection between Africa and Eurasia but affirmed "Egypt is African" with a "fluctuating distribution of African and Eurasian populations depending on historical circumstances".[40]

In a chapter review of UNESCO General History of Africa Volume II (which featured the conclusions of the 1974 symposium) by anthropologist and Egyptologist, Alain Anselin, (2025) the traditional historical view of a “wave of civilizing peoples” from the north to the south had been displaced by the weight of recent evidence in favour of a unifying movement from south to north.[41] He stated that recent research accumulated over three decades had confirmed the migration of peoples from the Sahara and regions south of Egypt to the Nile Valley.[42] This research had also situated Upper Egypt as the origin of pharaonic unification.[43] Anselin argued that this aligned with the position of the late Cheikh Anta Diop, who had attempted to "restore Egypt to its southern African hinterland".[44] Anselin referenced a range of specialist studies (anthropology, linguistics, genetics and archaeology) presented at a triennial conference in 2005 which he stated was a continuation of the 1974 recommendations.[45] This included a genetic study which quantified the "key impact" of Sub-Saharan populations and showed that the early pre-dynastic population of the Berber people of the Siwa Oasis in north-western Egypt had close demographic links with people of North-East Africa. He further described the value of other studies such as a Crubezy study which "traced the boundaries of the ancient Khoisan settlement to Upper Egypt, where its faint traces remain identifiable and Keita’s work, as the most groundbreaking", and that Cerny's team had identified close genetic and linguistic links between the peoples of Upper Egypt, North Cameroon (some of whom spoke Chadic languages) and Ethiopia (some of whom spoke Kushitic languages).[46]

Biological anthropological data

[edit]Skeletal biology

[edit]According to bioarchaeologist Nancy Lovell, the morphology of ancient Egyptian skeletons gives strong evidence that: "In general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas", but exhibited local variation in an African context.[47] S. O. Y. Keita, a biological anthropologist also reviewed studies on the biological affinities of the Ancient Egyptian population and characterised the skeletal morphologies of predynastic southern Egyptians as a "Saharo-tropical African variant". Keita also added that it is important to emphasize that whilst Egyptian society became more socially complex and biologically varied, the "ethnicity of the Niloto-Saharo-Sudanese origins did not change. The cultural morays, ritual formulae, and symbols used in writing, as far as can be ascertained, remained true to their southern origins."[48]

Megaliths from Nabta Playa displayed in the Aswan, Upper Egypt

Megaliths from Nabta Playa displayed in the Aswan, Upper Egypt

The early megalithic complex of Nabta Playa located in the Aswan Museum, Upper Egypt has exhibited close resemblances to Sub-Saharan and Sahelian ceremonial centres including structures found in Ethiopia, Senegal, regions north to Morocco and West Africa.[49] Anthropological studies have indicated linkages to Sub-Saharan and North African populations.[50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57]

A 1973 X-ray examination of southern king, Seqenenre Tao, by American Egyptologists, Kent Weeks and James E. Harris identified cranial similarities between his cranio-facial complex along with other Nubian and Old Kingdom Giza Skulls. In their view, this was supportive of scholarly interpretations that Sequenre Tao and his family may have held Nubian ancestry.[58][59]

James Harris and Fawzia Hussien (1991) conducted an X-ray survey on southern based 18th dynasty royal mummies and examined the mummified remains of Thutmose II. The results of the study determined that the mummy of Thutmose II had a craniofacial trait measurement that was common among Nubian populations.[60]

A 1992 study conducted by S.O.Y. Keita on First Dynasty crania from the royal tombs in Abydos, noted the predominant pattern was "Southern" or a "tropical African variant" (though others were also observed), which had affinities with Kerma Kushites.[61] The general results demonstrate greater affinity with Upper Nile Valley groups, but also suggest clear change from earlier craniometric trends. Moreover, analysis also found clear change from earlier craniometric trends, as "lower Egyptian, Maghrebian, and European patterns are observed also, thus making for great diversity". The gene flow and movement of northern officials to the important southern city may explain the findings.[62]

In 1996, Lovell and Prowse reported the presence of individuals buried at Naqada, Upper Egypt, in what they interpreted to be elite, high status tombs, showing them to be an endogamous ruling or elite segment who were significantly different from individuals buried in two other, apparently nonelite cemeteries, and more closely related morphologically to populations in Northern Nubia than those in Southern Egypt.[63]

Egyptologist Frank J. Yurco also considered the Badarians as exhibiting a "mix of North African and Sub-Saharan physical traits", and referenced older analysis of skeletal remains which "showed tropical African elements in the population of the earliest Badarian culture".[64]

In 2003, Japanese anthropologists Tsunehiko Hanihara, Hajime Ishida and Yukio Dodoet (2003) examined cranial traits from 70 human populations. The survey included samples from Predynastic Naqada (Upper Egypt) and 12th-13th dynasty Kushite Kerma (Sudan). In the context of the study, these samples were collectively classified as "North Africans" and other samples from Somalia along with Nigeria were classified as "Sub-Saharans", but lacked a specified dating period.[65] Overall, the samples from predynastic Naqada and Kerma clustered most closely and more remotely with European groups, whilst the other samples from Sub-Saharan Africa showed "significant separation from other regions, as well as diversity among themselves".[66]

In 2005, Keita examined Badarian crania from predynastic upper Egypt in comparison to various European and tropical African crania. He found that the predynastic Badarian series clustered much closer with the tropical African series. The comparative samples were selected based on "Brace et al.'s (1993) comments on the affinities of an upper Egyptian/Nubian epipalaeolithic series".[67]

In 2006, Barry Kemp found that skeletal samples from Elephantine (the border between Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia) from the 6th to 26th Dynasties showed very strong affinities with the Nubian population.[68] Comparatively, Kemp examined samples sourced from populations located in Africa, the Near East, and the Mediterranean.[69] Furthermore, he found that samples from northern Egypt (Merimde, Maadi, and the Wadi Digla) from before the 1st Dynasty showed no affinities with samples from Palestine and Byblos, and the proportions of members of these Egyptians group them with Africans, not Europeans.[70]

In 2006, C. Loring Brace and a team of anthropologists examined the skeletal morphology of humans populations from Neolithic and Bronze Age period. The analysis based on 24 craniofacial measures/variables, found close affinities between the Egyptian Naqada Bronze sample and Somalis, Nubia Bronze, Nubians and to a lesser extent, Tanzania Haya, Dahomey, and Congo.[71] On the other hand, lower similarities were found between the Egyptian Naqada sample and the other regions of the world, which included samples named Middle East, Berber, Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Italy amongst others, with the exception of the Israeli Fellaheen who also plotted with Naqada Bronze.[72]

In 2008, Keita found the early predynastic groups in Southern Egypt which included Badarian skeletal samples, were similar to Nile-Valley remains from areas to the south and north of Upper Egypt. Overall, the dynastic Egyptians (includes both Upper and Lower Egyptians) showed much closer affinities with these particular Northeast African populations. In his comparison to the various Egyptian series, Greeks, Somali/Horn, and Italians were used. He also concluded that more material was needed to make a firm conclusion about the relationship between the early Holocene Nile valley populations and later ancient Egyptians.[73]

Anthropological analysis conducted by Eric Crubézy (2002, 2010) on a Adaïma predynastic cemetery from 3700 CE and which contained 6,000 skeletons had found affinities with a southerly African population.[74]

In 2018, Godde assessed population relationships in the Nile Valley by comparing crania from 18 Egyptian and Nubian groups, spanning from Lower Egypt to Lower Nubia across 7,400 years. Overall, the results showed that the Mesolithic Nubian sample had a greater similarity with Naqada Egyptians. Similarly, Lower Nubian and Upper Egyptian samples clustered together. However, the Lower Egyptian samples formed a homogeneous unit, and there was a north–south gradient in the data set.[75]

In 2020, Godde analysed a series of crania, including two Egyptian (predynastic Badarian and Nagada series), a series of A-Group Nubians and a Bronze Age series from Lachish, Palestine. The two pre-dynastic series had strongest affinities, followed by closeness between the Nagada and the Nubian series. Further, the Nubian A-Group plotted nearer to the Egyptians and the Lachish sample placed more closely to Naqada than Badari. According to Godde the spatial-temporal model applied to the pattern of biological distances explains the more distant relationship of Badari to Lachish than Naqada to Lachish as gene flow will cause populations to become more similar over time.[76]

Egyptian historian and archaeological inspector at the Ministry of Antiquities, H. A. A. Ibrahim, examined the megalithic complex of Nabta Playa, Upper Egypt to understand the cultural and population influences of the Holocene on pre-dynastic Egypt (2025). She cited an anthropological study confirming the appearance of a Sub-Saharan high status child in a ceremonial centre and concluded that the megalithic structures had close resemblance to comparable structures in the Sahelian and Sub-Saharan regions of Africa.[77]

Dental studies

[edit]A 2002 study had found that Tasian dental markers were shown to similar be Sub-Saharan Africans and some also to North Africans. According to the researchers, it is possible that the population may have been a mix of both groups, but the sample size was concluded to be too small to make definitive statements.[78]

A 2006 bioarchaeological study on the dental morphology of ancient Egyptians in Upper Egypt by Joel Irish found that their dental traits were most similar to those of other Nile Valley populations, with more remote ties with Bronze Age to Christian period Nubians (e.g. A-Group, C-Group, Kerma) and other Afro-Asiatic speaking populations in Northeast Africa (Tigrean). Moreover, the Egyptian groups were generally distinct from the sampled West and Central African populations.[79] Among the samples included in the study is skeletal material from the Hawara tombs of Fayum, (from the Roman period) which clustered very closely with the Badarian series of the predynastic period. All the samples, particularly those of the Dynastic period, were significantly divergent from a Neolithic West Saharan sample from Lower Nubia. Biological continuity was also found intact from the dynastic to the post-pharaonic periods.[80]

Irish (2008) conducted a morphological comparison between the dental traits of human remains from Lower Nubian Neolithic sites at Gebel Ramlah (modern Southern Egypt) and Upper Nubian Neolithic sites from the cemeteries at R12 (modern Northern Sudan). Irish compared these remains to pooled dental samples from post-Neolithic Egyptians and Nubians to determine and distinguish biological affiliatations in the regional context. He concluded that the Lower Nubian samples of Gebel Ramlah and the Upper Nubian samples of R12 were not closely related biologically, whereas the post-Neolithic Egyptians and Nubians were closely related based on the Mean Measure of Divergence statistical analysis of 36 dental traits from the samples. This apparent homogeneity was attributed to population interaction stemming from a combination of trade, migration and genetic exchange along the River Nile, whereas the earlier Neolithic groups were more isolated from each other, both spatially and genetically.[81]

Biological anthropologist Shomarka Keita takes issue with the suggestion of Irish that Egyptians and Nubians were not primary descendants of the African epipaleolithic and Neolithic populations. Keita also criticizes him for ignoring the possibility that the dentition of the ancient Egyptians could have been caused by "in situ microevolution" driven by dietary change, rather than by racial admixture.[82]

Eric Crubézy (2010) found that 25% of the sampled children's teeth from a cemetery in Adaima, Upper Egypt had "Bushmen" upper canines typical of people from Khoi-San which "confirmed the African origin of the Adamia population.[83]

Limb proportions

[edit]Robins and Shute (1983) performed X-ray measurements on the physical proportions of Upper Egyptian rulers such as Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Tutankhamun. The authors reported that the limbs of the pharaohs, like those of other Ancient Egyptians, had "negroid characteristics", in that the distal segments were relatively long in comparison with the proximal segments. An exception was Ramesses II, who appears to have had short legs below the knees.[84]

A 2003 study performed by Sonia Zakrzewski had found Upper Egyptians, with sample collections sourced from the Badarin and Middle Kingdom eras, as having tropical body proportions.[85] She described their proportions as measured in the raw data to be "super-negroid" (i.e. the limb indices are relatively longer than in many "African" populations) in line with the results of the Robbins study (1983).[86] Nonetheless, she proposed that the apparent development of an increasingly African body plan over time may also be due to Nubian mercenaries being included in the Middle Kingdom sample.[87] Overall, she found that the available samples featured in the study "relatively clustered together" as compared to other populations. Zakrzewski cautioned that the results were provisional due to the limited small sizes and lack of skeletal material that "cross-cuts all social and economic groups within each time period".[88]

Raxter (2014) examined skeletal collection of 492 males and 528 females, all adults from the Predynastic and Dynastic Periods, a time spanning c. 5500 BCE-600 CE. Overall, she found that Ancient Egyptians have more tropically adapted limbs in comparison to body breadths, the latter she interpreted to be suggestive of intermediate when plotted against higher and lower latitude populations.[89] Her results identified a gradation with Upper Egyptians and Lower Nubians having shared affinities whilst Lower Egyptians were more closely linked with Southern European populations.[90] Raxter summarised that her results might also suggest early Mediterranean or Near Eastern influence in Northeast Africa.[91]

Other biological data

[edit]Shomarka Keita reported that a 2005 study on mummified remains found that "some Theban nobles had a histology which indicated notably dark skin".[92]

In 2023, Christopher Ehret reported that physical anthropological findings, performed by Keita and Zakrzewski, on the "major burial sites of those founding locales of ancient Egypt in the fourth millennium BCE, notably El-Badari as well as Naqada, show no demographic indebtedness to the Levant". Ehret specified that these studies revealed cranial and dental affinities with "closest parallels" to other longtime populations in the surrounding areas of Northeastern Africa "such as Nubia and the northern Horn of Africa". He further commented that the Naqada and Badarian populations did not migrate "from somewhere else but were descendants of the long-term inhabitants of these portions of Africa going back many millennia".[93]

Genetic studies

[edit]Ancient samples

[edit]Multiple forms of genetic analysis have been conducted on the 18th dynasty royal Amarna mummies (including pharaohs Tutankhamun, Amenhotep III and Akhenaten) that were based in Thebes, Upper Egypt with conflicting set of results.[94][95]

Keita, Gourdine and Anselin performed STR analysis on the Theban royal mummies, which derived from a 2010 genetic study performed by Zahi Hawass and his team, to determine the population affinities. According to Gourdine (2025), this he analysis had found “that they had strong affinities with current sub-Saharan populations: 41 per cent to 93.9 per cent for sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 4.6 per cent to 41 per cent for Eurasia and 0.3 per cent to 16 per cent for Asia (Gourdine, 2018).”[96] Gourdine also referenced supporting analysis conducted by DNA Tribes company, which specialized in genetic genealogy and had large datasets, with the latter having identified strong affinities between the Amarna royal mummies and Sub-Saharan African populations.”[97]

Hawass and his team had produced another study in 2020 which identified haplogroup R1b and mtDNA K genetic markers in the Amarna royal mummies and interpreted this to show strong genetic affinities with European and West Asian populations.[98][99]

In another 2025 multidisciplinary review, noting the R1b M89 haplogroup subtype identified among the three Amarna pharaohs (Tutankhamun, Amenhotep III and Akhenaten) was not further specified.[100] The authors also stated that the R1b haplogroup usually interpreted as indicating a back migration to Africa from or via the Near East could have been attributed to Asian back migration or trans-Saharan connections as the genetic marker is found at relative high frequencies among Chadic populations.[101] Referencing a Short Tandem Report (STR) autosomal background analysis on the Amarna royal mummies, performed by Keita in an earlier publication, the authors considered this analysis could suggest closer trans-Saharan connections.[102] Ehret et al also disclosed through personal communication with the Gad team that "other eighteenth dynasty lineages in the Amarna period were found to be E1b1a (Gad et al 2020)".[103] The authors further postulated that association of the palaeolithic Asian lineage (R1B) and an affiliation that is tropical African (E1b1a) is an example of admixture found in some Nile Valley populations, and that a mixture of lineages could illustrate Egypt being near a crossroads.[104]

Modern samples

[edit]Genetic analysis of a modern Upper Egyptian population in Adaima by Eric Crubézy had identified genetic markers common across Africa, with 71% of the cases carrying E1b1 haplogroup and 3% carrying the L0f mitochondrial haplogroup.[45] A secondary review published in 2025 noted the results were preliminary and need to be confirmed by other laboratories with new sequencing methods.[45]

Anthropologist Alain Anselin found the distribution of linguistic, archaeological data to be consistent with initial genetic findings on Upper Egyptian population in Gurna which had a remnant of high M1 haplogroup and sub-Saharan affinities.[105] This has been interpreted to suggest that the current population structure of Egypt may be the result of neighbouring influences on the ancestral population.[106] Anselin also suggested that the combination of historical genetics and recent archaeological excavations in the Western Desert could contribute to the peopling of Egypt for which Saharan affinities had been identified in a previous, interdisciplinary review.[107]

Another 2004 mtDNA study featured the Gurna individuals samples, and clustered them together with the Ethiopian and Yemeni groups, in between the Near Eastern and other African sample groups.[108]

Compiled genetic publications had found high frequency of E haplogroup subclades across Egypt, including among Egyptian Copts in Adaima, Upper Egypt and émigré Coptic communities in Sudan.[109] Other haplogroups with a notable occurrence in the Egyptian populations have included the J and R haplogroups.[110] The E-M35 haplogroup subclade is found among all Afro-Asiatic speaking regions, with the M-78 clade now commonly thought to have arisen in either Sudan or Egypt.[111]

Cultural affinities

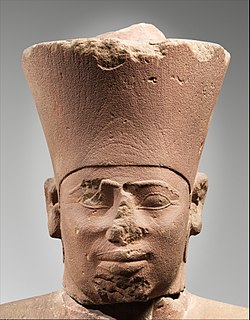

[edit] Statue of Mentuhotep II, 11th dynasty ruler, originated from Thebes, southern Egypt.[112]

Statue of Mentuhotep II, 11th dynasty ruler, originated from Thebes, southern Egypt.[112]

Upper Egypt is considered to have formed the pre-dominant basis for the cultural development of Pharaonic Egypt and the Proto-dynastic kings emerged from the Naqada region.[113][114] Several dynasties of southern or Upper Egyptian origin, which included the 11th, 12th, 17th, 18th and 25th dynasties, reunified and reinvigorated pharaonic Egypt after periods of fragmentation.[115]

In the view of American Egyptologist Frank J. Yurco,

"The XIIth Dynasty (1991-1786 B.C.E.) originated from the Aswan region. As expected, strong Nubian features and dark coloring are seen in their sculpture and relief work. This dynasty ranks as among the greatest, whose fame far outlived its actual tenure on the throne."[116]

An assemblage of older scholarship have identified a common African substratum for early Egyptian cultural practices. Central African tool designs are featured in the Badarian and Naqada archaeological sites.[117] According to archaeologist, Charles Thurstan Shaw, "the early cultures of Merimde, Badari, Naqadi I and II are essentially African and early African social customs and religious beliefs were the root and foundation of Egyptian way of life."[118]

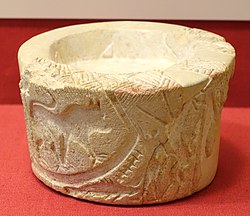

Qustul Incense Burner, excavated from a royal Nubian tomb in Lake Nasser, considered among the earliest representations of the White Crown Hedjet in Upper Egypt.[119]

Qustul Incense Burner, excavated from a royal Nubian tomb in Lake Nasser, considered among the earliest representations of the White Crown Hedjet in Upper Egypt.[119]

Archaeologist Bruce Williams has advanced the view that Nubians participated with the first dynastic counterparts in the development of the pharaonic civilization.[120] Williams also clarified in 1987 that his discovery of the Qutsul incense burner advanced no claim of a Nubian origin or genesis for the pharaonic monarchy but that excavations had shown Nubian linkages and contributions.[121] He maintained that detailed, archaeological evidence has found cemeteries of tombs situated in Qustul, Nubia vastly greater and wealthier in size than the Abydos tombs of the first dynastic rulers.[122]

Excavations at Hierakonpolis (Upper Egypt) found archaeological evidence of ritual masks similar to those used further south of Egypt, and obsidian linked to Ethiopian quarry sites.[123] Frank Yurco stated that depictions of pharonic iconography such as the royal crowns, Horus falcons and victory scenes were concentrated in the Upper Egyptian Naqada culture and A-Group Lower Nubia.[124]

Anthropologist Joseph Vogel (1997) stated "The period when sub-Saharan Africa was most influential in Egypt was a time when neither Egypt, as we understand it culturally, nor the Sahara, as we understand it geographically, existed. Populations and cultures now found south of the desert roamed far to the north. The culture of Upper Egypt, which became dynastic Egyptian civilization, could fairly be called a Sudanese transplant."[125]

Similarly, Christopher Ehret, historian and linguist, stated that the cultural practice of sacral chiefship and kingship which emerged in Upper Egypt in the fourth millennium had originated centuries earlier in Nubia and the Middle Nile south of Egypt. He based this judgement on supporting, archaeological and comparative ethnographic evidence.[126] Ehret also reviewed the excavations from the neighbouring Lower Nubia which demonstrated that “The Qustul elite and ruler in the second half of the fourth millennium participated together with their counterparts in the communities of the Naqada culture of southern Egypt in creating the emerging culture and paraphernalia of pharaonic culture”.[127] Ehret argued that archaeological data had presented cultural continuity between the Afian period and Holocene epoch, with existing populations of Upper Egypt incorporating new crops and food productions from the Levant without evidence of any notable population intrusions into that region during the seventh and sixth millennia.[128]

Anthropologist Alain Anselin cited recent archaeological data compiled which had identified Tasian and Badarian Nile Valley sites as peripheral networks of earlier African cultures that featured the movement of Badarian, Saharan, Nubian, and Nilotic populations.[129] American archaeologist, Bruce Williams, has stated "The Tasian Period is significantly related to the Neolithic of Sudanese-Saharan tradition as found just north of Khartoum and near Dongola in Sudan".[130][131]

Stan Hendrick, John Coleman Darnell and Maria Gatto in 2012 excavated petroglyphic engravings from Nag el-Hamdulab to the north of Aswan, in southern Egypt, which featured representations of a boat procession, solar symbolism and the earliest known depiction of the White Crown with an estimated dating range between 3200 BCE and 3100 BCE.[132]

Maria Gatto (2014) stated that archaeological research in the Aswan area had identified cultural admixture in the boundary region of the first cataract of the Nile during the fourth millennium BCE.[133] According to Gatto, the advent of the Naqada culture lead to a divergence between Egyptian and Nubian identities.[134] This culture was later spread northwards in Egypt and southwards in Nubia. Prior to this period, earlier Egyptian cultures (Tarifian, Badarian and Tasian) in the southern region were strongly similar to Nubian and Nilotic pastoral traditions and the cultural substratum in Upper Egypt was Nubian mostly-related.[135]

In 2018, American anthropologist Stuart Tyson Smith, reviewed evidence which indicated linkages between the Upper Egyptian region, the Sahara and the Sudanese Nubia.[136] He argued that the cultural features which characterised the Egyptian civilisation were "widely distributed in north-eastern Africa but not in western Asia" and this had earlier origins in the Saharan wet phase period.[137]

Linguistic connections

[edit]American Egyptologist, Frank Yurco, affirmed that "Egyptian writing arose in Naqadan Upper Egypt and A-Group Lower Nubia, and not in the Delta cultures, where the direct Western Asian contact was made, further vitiates the Mesopotamian-influence argument".[138]

Viktor Cerny's research team had identified close biological and linguistic links between the peoples of Upper Egypt, North Cameroon (some of whom spoke Chadic languages) and Ethiopia (some of whom spoke Cushitic languages).[139]

Anthropologist Alain Anselin had issued a comparative review of Afro-Asiatic language families which suggested earliest speakers of the Egyptian language could be located in regions south of Upper Egypt or the Saharan hinterland.[140] In his concluding passage, he found it plausible that early Upper Egyptian cultures were a crossroads for North Eastern African groups such as the Beja peoples.[141] From this interpretation, Anselin, found the most probable scenario that some Saharao-Nubian populations moved southwards to regions such as Darfur whilst others had migrated to Upper Egyptian territories such as Bir Sahara, Nabta Playa, Gebel Ramlah, and Nekhen/Hierakonpolis.[142] Anselin viewed this to hold wider significance for glottochronology and cultural anthropology.[143]

According to historical linguist, Christopher Ehret, the material cultural indicators of the Nabta Playa complex in Upper Egypt, correspond with the conclusion that the inhabitants of the wider Nabta Playa region were a Nilo-Saharan-speaking population.[144]

British linguist, Roger Blench, observed that pockets of Nilo-Saharan speakers are found in Upper Egypt. He further added that it was possible that early Afro-Asiatic speakers had domesticated wild cattle in the Egyptian-Sudanese border 10,000 years ago.[145]

The Cushitic language which is a sub-branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family was spoken in Lower Nubia, an ancient region which extends from Upper Egypt to Northern Sudan, before the arrival of North Eastern Sudanic languages in the Middle Nile Valley.[146][147][148][149]

List of rulers of prehistoric Upper Egypt

[edit]The following list may not be complete (there are many more of uncertain existence):

| Name | Image | Comments | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elephant | End of 4th millennium BC | ||

| Bull | 4th millennium BC | ||

| Scorpion I | Oldest tomb at Umm el-Qa'ab had scorpion insignia | c. 3200 BC? | |

| Iry-Hor |

|

Possibly the immediate predecessor of Ka. | c. 3150 BC? |

| Ka[150][151] |

|

May be read Sekhen rather than Ka. Possibly the immediate predecessor of Narmer. | c. 3100 BC |

| Scorpion II |

|

Potentially read Serqet; possibly the same person as Narmer. | c. 3150 BC |

| Narmer |

|

The king who combined Upper and Lower Egypt.[152] | c. 3150 BC |

List of nomes

[edit]| Number | Ancient Name | Capital | Modern Capital | Translation | God |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ta-khentit | Abu / Yebu (Elephantine) | Aswan | The Frontier/Land of the Bow | Khnemu |

| 2 | Wetjes-Hor | Djeba (Apollonopolis Magna) | Edfu | Throne of Horus | Horus-Behdety |

| 3 | Nekhen | Nekhen (Hierakonpolis) | al-Kab | Shrine | Nekhebet |

| 4 | Waset | Niwt-rst / Waset (Thebes) | Karnak | Sceptre | Amun-Ra |

| 5 | Harawî | Gebtu (Coptos) | Qift | Two Falcons | Min |

| 6 | Aa-ta | Iunet / Tantere (Tentyra) | Dendera | Crocodile | Hathor |

| 7 | Seshesh | Seshesh (Diospolis Parva) | Hu | Sistrum | Hathor |

| 8 | Ta-wer | Tjenu / Abjdu (Thinis / Abydos) | al-Birba | Great Land | Onuris |

| 9 | Min | Apu / Khen-min (Panopolis) | Akhmim | Min | Min |

| 10 | Wadjet | Djew-qa / Tjebu (Antaeopolis) | Qaw al-Kebir | Cobra | Hathor |

| 11 | Set | Shashotep (Hypselis) | Shutb | Set animal | Khnemu |

| 12 | Tu-ph | Per-Nemty (Hieracon) | At-Atawla | Viper Mountain | Horus |

| 13 | Atef-Khent | Zawty (Lycopolis) | Asyut | Upper Sycamore and Viper | Apuat |

| 14 | Atef-Pehu | Qesy (Cusae) | al-Qusiya | Lower Sycamore and Viper | Hathor |

| 15 | Wenet | Khemenu (Hermopolis) | Hermopolis | Hare[153] | Thoth |

| 16 | Ma-hedj | Herwer? | Hur? | Oryx[153] | Horus |

| 17 | Anpu | Saka (Cynopolis) | al-Kais | Anubis | Anubis |

| 18 | Sep | Teudjoi / Hutnesut (Alabastronopolis) | el-Hiba | Set | Anubis |

| 19 | Uab | Per-Medjed (Oxyrhynchus) | el-Bahnasa | Two Sceptres | Set |

| 20 | Atef-Khent | Henen-nesut (Heracleopolis Magna) | Ihnasiyyah al-Madinah | Southern Sycamore | Heryshaf |

| 21 | Atef-Pehu | Shenakhen / Semenuhor (Crocodilopolis, Arsinoë) | Faiyum | Northern Sycamore | Khnemu |

| 22 | Maten | Tepihu (Aphroditopolis) | Atfih | Knife | Hathor |

Governorates and large cities

[edit]Nowadays, Upper Egypt forms part of these 7 governorates:

Large cities located in Upper Egypt:

- Beni Suef

- El Fashn

- Beni Mazar

- Minya

- Mallawi

- Dairut

- Asyut

- Tahta

- Sohag

- Girga

- Nag Hammadi

- Qena

- Luxor

- Edfu

- Aswan

See also

[edit]- Sa'idi people

- Copts

- Egyptians

- Lower Nubia

- Ta-Seti

- Nubian people

- Beja people

- Upper and Lower Egypt

- Geography of Egypt

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The title was first used by Prince Farouk, the son and heir of King Fouad I. Prince Farouk was officially named Prince of the Sa'id on 12 December 1933.[17]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Upper Egypt". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ Ermann & Grapow 1982, Wb 5, 227.4-14.

- ^ Ermann & Grapow (1982), Wb 4, 477.9-11

- ^ Leichty, Erle (2011). The Royal Inscriptions of Esarhaddon, King of Assyria (680-669 BC) (PDF). Vol. 4. Eisenbrauns. p. 135. doi:10.1515/9781575066462. ISBN 978-1-57506-646-2. JSTOR 10.5325/j.ctv1bxh5jz: pa-tú-ri-si.

}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ אחיטוב, שמואל (2003). "ירמיהו במצרים" [Jeremiah in Egypt]. Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. 27: 36. JSTOR 23629799.

- ^ See list of nomes. Maten (Knife land) is the northernmost nome in Upper Egypt on the right bank, while Atef-Pehu (Northern Sycamore land) is the northernmost on the left bank. Brugsch, Heinrich Karl (2015). A History of Egypt under the Pharaohs. Vol. 1. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 487., originally published in 1876 in German.

- ^ Brink, Edwin C. M. van den (1992). "The Nile Delta in Transition: 4th.-3rd. Millennium B.C." Proceedings of the Seminar Held in Cairo, 21.-24. October 1990, at the Netherlands Institute of Archaeology and Arabic Studies. E.C.M. van den Brink. ISBN 978-965-221-015-9.

- ^ Griffith, Francis Llewellyn, A Collection of Hieroglyphs: A Contribution to the History of Egyptian Writing, the Egypt Exploration Fund 1898, p. 56

- ^ Bard & Shubert (1999), p. 371

- ^ David (1975), p. 149

- ^ Roebuck (1966), p. 51

- ^ a b c d e Roebuck (1966), pp. 52–53

- ^ Roebuck (1966), p. 53

- ^ Chauveau (2000), p. 68

- ^ Ballais (2000), p. 133

- ^ Ballais (2000), p. 134

- ^ Brice (1981), p. 299

- ^ Brace, 1993. Clines and clusters

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (April 2007). "Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 501–509. Bibcode:2007AJPA..132..501Z. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569. PMID 17295300. When Mahalanobis D2 was used, the Naqadan and Badarian Predynastic samples exhibited more similarity to Nubian, Tigrean, and some more southern series than to some mid- to late Dynasticseries from northern Egypt (Mukherjee et al., 1955). The Badarian have been found to be very similar to a Kerma sample (Kushite Sudanese), using both the Penrose statistic (Nutter, 1958) and DFA of males alone (Keita,1990). Furthermore, Keita considered that Badarian males had a southern modal phenotype, and that together with a Naqada sample, they formed a southern Egyptian cluster as tropical variants together with a sample from Kerma

- ^ Tracy L. Prowse, Nancy C. Lovell. "Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 101, Issue 2, October 1996, pp. 237-246

- ^ Godde, Kane. "A biological perspective of the relationship between Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East during the Predynastic period (2020)". Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Mokhtar, Gamal, ed. (1981). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. UNESCO International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa; Heinemann Educational Books; University of California Press. pp. 20–21, 148. ISBN 978-0-520-03913-1. The difference in behaviour between two populations of similar ethnic composition throws significant light on an apparently abnormal fact: one of them adopted and perhaps even invented, a system of writing, while the other, which was aware of that writing, disdained it

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (September 1990). "Studies of ancient crania from northern Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 83 (1): 35–48. Bibcode:1990AJPA...83...35K. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330830105. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 2221029.

- ^ Strohaul, Eugene. "Anthropology of the Egyptian Nubian Men - Strouhal - 2007 - ANTHROPOLOGIE" (PDF). Puvodni.MZM.cz: 115.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (November 2005). "Early Nile Valley Farmers From El-Badari: Aboriginals or 'European' AgroNostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered with Other Data". Journal of Black Studies. 36 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912. ISSN 0021-9347. S2CID 144482802.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka. "Analysis of Naqada Predynastic Crania: a brief report (1996)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-12-05. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- ^ "There is now a sufficient body of evidence from modern studies of skeletal remains to indicate that the ancient Egyptians, especially southern Egyptians, exhibited physical characteristics that are within the range of variation for ancient and modern indigenous peoples of the Sahara and tropical Africa. The distribution of population characteristics seems to follow a clinal pattern from south to north, which may be explained by natural selection as well as gene flow between neighboring populations. In general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas.”Lovell, Nancy C. (1999). "Egyptians, physical anthropology of". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. pp. 328–331. ISBN 0415185890.

- ^ “The data clearly suggests that the population in southern Egypt became more diverse as the society more complex (Keita 1992). Egyptian society seems never to have been “closed”, and it is hard to believe that the modal phenotype could have remain unchanged, especially if social and sexual collection were operating. However, it is important to emphasize that, while the biology changed with increasing local social complexity, the ethnicity of Niloto-Saharo-Sudanese origins did not change. The cultural morays, ritual formulae, and symbols used in writing, as far as can be ascertained, remained true to their southern origins”.Keita, S. O. Y. (1993). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa. 20: 129–154. doi:10.2307/3171969. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3171969. S2CID 162330365.

- ^ p.85–“The physical anthropological findings from the major burial sites of those founding locales of ancient Egypt in the millennium BCE, notably El-Badari as well as Naqada, show no demographic indebtedness to the Levant. They reveal instead a population with cranial and dental features with closest parallels of those of other longtime populations of the surrounding areas of northeastern Africa, such as Nubia and the northern Horn of Africa. Members of this population did not come from somewhere else but were descendants of the long-term inhabitants of these portions of Africa going back many millennia.”Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 83–86, 97, 167–169. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ p.355 - “The importance of iconographic sources was emphasized in the main. Säve-Söderbergh and Leclant stressed that the links indicated by cave paintings between the vast expanses of the Sahara and the banks of the Nile nodded to a migration of peoples of the Sahara and groups from the South to the valley –something confirmed by research over the last thirty years. Diop set out to return Egypt to its southern African hinterland by systematically using Pharaonic statues and art to support his point of view. Although a debate on the north-south orientation of a ‘civilizing’ wave of peoples in the valley had prevailed up to that point, the avalanche of new data now made this idea redundant, suggesting instead the image of a growing and unifying political movement in the valley from south to north that repositioned its starting point back in time: in Upper Egypt, digs at the Uj tomb of King Scorpion at the Abydos necropolis push back the origin of the first Horus back to circa 3250 BCE, and the resumption of excavations at Nekhen led to the exhumation of the famous ‘Elephant Kings’ of Hierakonpolis (Nekhen) which have no inscriptions and date back even further to circa 3700 BCE.”

p.356 - “It quantified the key impact of sub-Saharan populations and found a clear link between the Siwi and the peoples of North-East Africa. We could continue with work by Zakrzewski on the predynastic population of Nekhen, investigations by Crubezy which traced the boundaries of the ancient Khoisan settlement to Upper Egypt, where its faint traces remain identifiable, and Keita’s work, as the most groundbreaking.”'

p.356 - “Hence the work by Cerny’s team highlighting the close links between the peoples of Upper Egypt, North Cameroon and Ethiopia – the Cameroon people living in the Mandara mountains speaking Chadic languages, and the Ethiopians speaking Kushitic languages, prior to Ge’ez being spread throughout the region during the Aksumite period. This broadens the linguistic debate to include language families that had been little studied or used in comparisons that have long focused on the East.” Anselin, Alain. "Review of Ancient Civilizations of Africa: General History of Africa Volume II " in (General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 355–75. - ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (April 2007). "Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (4): 501–509. Bibcode:2007AJPA..132..501Z. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569. PMID 17295300. When Mahalanobis D2 was used, the Naqadan and Badarian Predynastic samples exhibited more similarity to Nubian, Tigrean, and some more southern series than to some mid- to late Dynasticseries from northern Egypt (Mukherjee et al., 1955). The Badarian have been found to be very similar to a Kerma sample (Kushite Sudanese), using both the Penrose statistic (Nutter, 1958) and DFA of males alone (Keita,1990). Furthermore, Keita considered that Badarian males had a southern modal phenotype, and that together with a Naqada sample, they formed a southern Egyptian cluster as tropical variants together with a sample from Kerma

- ^ "Southern Egypt and Nubia are geographically co-extensive, with populations grading into each other. The absorption of Qustul’s people would have reinforced this. There is biological overlap of these populations in origin, but ongoing admixture is also apparent."Keita, S. O. Y. (September 2022). "Ideas about "Race" in Nile Valley Histories: A Consideration of "Racial" Paradigms in Recent Presentations on Nile Valley Africa, from "Black Pharaohs" to Mummy Genomest". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections.

- ^ Hassan, Fekri (20 May 2021). "The African Dimension of Egyptian Origins (May 2021)".

- ^ "Guardian Figure". Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2025.

- ^ Lobban, Richard A. Jr. (10 April 2021). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Nubia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781538133392.

- ^ Van de Mieroop, Marc (2021). A history of ancient Egypt (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex. p. 99. ISBN 978-1119620877.

}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mokhtar, Gamal. General history of Africa, II: Ancient civilizations of Africa. p. 20-25.

- ^ Mokhtar, Gamal. General history of Africa, II: Ancient civilizations of Africa. p. 20-25.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. p. LVIII.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 356–357.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 356–357.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 356–357.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 356–357.

- ^ a b c Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. p. 728.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 356–357.

- ^ Lovell, Nancy C. (1999). "Egyptians, physical anthropology of". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. pp. 328–331. ISBN 0415185890. There is now a sufficient body of evidence from modern studies of skeletal remains to indicate that the ancient Egyptians, especially southern Egyptians, exhibited physical characteristics that are within the range of variation for ancient and modern indigenous peoples of the Sahara and tropical Africa. The distribution of population characteristics seems to follow a clinal pattern from south to north, which may be explained by natural selection as well as gene flow between neighboring populations. In general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (1993). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa. 20: 129–154. doi:10.2307/3171969. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3171969. S2CID 162330365.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 469, 705–722.

- ^ Wendorf, Fred (2001). Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 489–502. ISBN 978-0-306-46612-0.

- ^ Ancient Astronomy in Africa Archived 3 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wendorf, Fred (2001). Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. Springer. p. 525. ISBN 978-0-306-46612-0.

- ^ Irish, Joel D. (2001). "Human Skeletal Remains from Three Nabta Playa Sites". Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. pp. 521–528. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0653-9_18. ISBN 978-1-4613-5178-8 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara: Volume 1: The Archaeology of Nabta Playa, by By Fred Wendorf, Romuald Schild (chapter 18: Human Skeletal Remains from Three Nabta Playa Sites, by Joel D. Irish), p. 125-128, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Wendorf, Fred (2001). Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 489–502. ISBN 978-0-306-46612-0.

- ^ McKim Malville, J. (2015). "Astronomy at Nabta Playa, Southern Egypt". Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. Springer. pp. 1080–1090. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_101. ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1.

- ^ Y., Keita, S. O. (1990). "Studies of ancient crania from northern Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 83 (1): 35–48. Bibcode:1990AJPA...83...35K. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330830105. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 2221029.

}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ F. J. Yurco. "'Were the ancient Egyptians black or white?'". Biblical Archaeology Review. (Vol 15, no. 5, 1989): 35–37.

- ^ Harris, James E.; Hussien, Fawzia (September 1991). "The identification of the Eighteenth Dynasty royal mummies; a biological perspective". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 1 (3–4): 235–239. doi:10.1002/oa.1390010317. ISSN 1047-482X. Archived from the original on 20 April 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (1992). "Further studies of crania from ancient Northern Africa: An analysis of crania from First Dynasty Egyptian tombs, using multiple discriminant functions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 87 (3): 245–254. Bibcode:1992AJPA...87..245K. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330870302. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 1562056.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (1992). "Further studies of crania from ancient Northern Africa: An analysis of crania from First Dynasty Egyptian tombs, using multiple discriminant functions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 87 (3): 245–254. Bibcode:1992AJPA...87..245K. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330870302. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 1562056.

- ^ Tracy L. Prowse, Nancy C. Lovell. Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 101, Issue 2, October 1996, Pages: 237–246

- ^ Yurco, Frank (1996). "An Egyptological Review". In Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (eds.). Black Athena Revisited. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 65–67. ISBN 978-0-8078-4555-4.

- ^ Hanihara, Tsunehiko; Ishida, Hajime; Dodo, Yukio (July 2003). "Characterization of biological diversity through analysis of discrete cranial traits". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 241–251. Bibcode:2003AJPA..121..241H. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10233. PMID 12772212.

- ^ Hanihara, Tsunehiko; Ishida, Hajime; Dodo, Yukio (July 2003). "Characterization of biological diversity through analysis of discrete cranial traits". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 241–251. Bibcode:2003AJPA..121..241H. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10233. PMID 12772212.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. (November 2005). "Early Nile Valley Farmers From El-Badari: Aboriginals or "European"AgroNostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data". Journal of Black Studies. 36 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912. ISSN 0021-9347. S2CID 144482802.

- ^ Kemp, Barry J. (7 May 2007). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation. Routledge. pp. 46–58. ISBN 978-1-134-56388-3.

- ^ Kemp, Barry J. (7 May 2007). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation. Routledge. pp. 46–58. ISBN 978-1-134-56388-3.

- ^ Kemp, Barry J. (7 May 2007). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation. Routledge. pp. 46–58. ISBN 978-1-134-56388-3.

- ^ Brace, C. Loring; et al. (2006). "The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form". PNAS. 103 (1): 242–247. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..242B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102. PMC 1325007. PMID 16371462.

- ^ Brace, C. Loring; et al. (2006). "The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form". PNAS. 103 (1): 242–247. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..242B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102. PMC 1325007. PMID 16371462.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y.; Boyce, A. J. (April 2008). "Temporal variation in phenetic affinity of early Upper Egyptian male cranial series". Human Biology. 80 (2): 141–159. doi:10.3378/1534-6617(2008)80[141:TVIPAO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0018-7143. PMID 18720900. S2CID 25207756.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 724–731.

- ^ Godde, K. (July 2018). "A new analysis interpreting Nilotic relationships and peopling of the Nile Valley". Homo: Internationale Zeitschrift für die Vergleichende Forschung am Menschen. 69 (4): 147–157. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2018.07.002. ISSN 1618-1301. PMID 30055809. S2CID 51865039.

- ^ Godde, Kane. "A biological perspective of the relationship between Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East during the Predynastic period (2020)". Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 705–723.

- ^ Friedman, Renee; Hobbs, Joseph (2002-01-01). "Friedman Hobbs 2002 A 'Tasian' Tomb in Egypt's Eastern Desert". Egypt and Nubia. Gifts of the Desert, Edited by R. Friedman.

- ^ Irish, J. D.; Konigsberg, L. (2007). "The ancient inhabitants of Jebel Moya redux: measures of population affinity based on dental morphology". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 17 (2): 138–156. doi:10.1002/oa.868.

- ^ Irish, J. D.; Konigsberg, L. (2007). "The ancient inhabitants of Jebel Moya redux: measures of population affinity based on dental morphology". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 17 (2): 138–156. doi:10.1002/oa.868.

- ^ Irish, Joel (1 January 2008). "A dental assessment of biological affinity between inhabitants of the Gebel Ramlah and R12 Neolithic sites".

- ^ S.O.Y. Keita, S. O. Y. (1995). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". International Journal of Anthropology. 10 (2–3): 107–123. doi:10.1007/BF02444602. S2CID 83660108.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 723–41.

- ^ Robins, G.; Shute, C. C. D. (1 July 1983). "The physical proportions and living stature of New Kingdom pharaohs". Journal of Human Evolution. 12 (5): 455–465. Bibcode:1983JHumE..12..455R. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(83)80141-9. ISSN 0047-2484.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (July 2003). "Variation in ancient Egyptian stature and body proportions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 219–229. Bibcode:2003AJPA..121..219Z. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10223. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 12772210. S2CID 9848529.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (July 2003). "Variation in ancient Egyptian stature and body proportions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 219–229. Bibcode:2003AJPA..121..219Z. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10223. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 12772210. S2CID 9848529.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (July 2003). "Variation in ancient Egyptian stature and body proportions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 219–229. Bibcode:2003AJPA..121..219Z. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10223. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 12772210. S2CID 9848529.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (July 2003). "Variation in ancient Egyptian stature and body proportions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 219–229. Bibcode:2003AJPA..121..219Z. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10223. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 12772210. S2CID 9848529.

- ^ Raxter, Michelle (2011). Egyptian Body Size: A Regional and Worldwide Comparison (PhD dissertation). University of South Florida.

- ^ Raxter, Michelle (2011). Egyptian Body Size: A Regional and Worldwide Comparison (PhD dissertation). University of South Florida.

- ^ Raxter, Michelle (2011). Egyptian Body Size: A Regional and Worldwide Comparison (PhD dissertation). University of South Florida.

- ^ Keita Shomarka. (2022). "Ancient Egyptian "Origins and "Identity" In Ancient Egyptian society : challenging assumptions, exploring approaches. Abingdon, Oxon. pp. 111–122. ISBN 978-0367434632.

}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 83–86, 97. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Gad, Yehia (2020). "Maternal and paternal lineages in King Tutankhamun's family". Guardian of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of Zahi Hawass. Czech Institute of Egyptology. pp. 497–518. ISBN 978-80-7308-979-5.

- ^ Gad, Yehia (2020). "Insights from ancient DNA analysis of Egyptian human mummies: clues to disease and kinship". Human Molecular Genetics. 30 (R1): R24–R28. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddaa223. ISSN 0964-6906. PMID 33059357.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. p. 730.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. p. 730.

- ^ Gad, Yehia (2020). "Maternal and paternal lineages in King Tutankhamun's family". Guardian of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of Zahi Hawass. Czech Institute of Egyptology. pp. 497–518. ISBN 978-80-7308-979-5.

- ^ Gad, Yehia (2020). "Insights from ancient DNA analysis of Egyptian human mummies: clues to disease and kinship". Human Molecular Genetics. 30 (R1): R24–R28. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddaa223. ISSN 0964-6906. PMID 33059357.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David; Ehret, Christopher; A Brandt, Steven; Keita, Shomarka (9 June 2025). "Afrasian linguistics" in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology and Language (Mark Hudson, Martine Robbeets (eds) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 540–569. ISBN 978-0-19-269455-3.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David; Ehret, Christopher; A Brandt, Steven; Keita, Shomarka (9 June 2025). "Afrasian linguistics" in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology and Language (Mark Hudson, Martine Robbeets (eds) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 540–569. ISBN 978-0-19-269455-3.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David; Ehret, Christopher; A Brandt, Steven; Keita, Shomarka (9 June 2025). "Afrasian linguistics" in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology and Language (Mark Hudson, Martine Robbeets (eds) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 540–569. ISBN 978-0-19-269455-3.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David; Ehret, Christopher; A Brandt, Steven; Keita, Shomarka (9 June 2025). "Afrasian linguistics" in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology and Language (Mark Hudson, Martine Robbeets (eds) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 540–569. ISBN 978-0-19-269455-3.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David; Ehret, Christopher; A Brandt, Steven; Keita, Shomarka (9 June 2025). "Afrasian linguistics" in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology and Language (Mark Hudson, Martine Robbeets (eds) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 540–569. ISBN 978-0-19-269455-3.

- ^ Anselin, Alain (2011). "Some notes about an Early African Pool of Cultures" in Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1-4073-0760-2.

- ^ Anselin, Alain (2011). "Some notes about an Early African Pool of Cultures" in Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1-4073-0760-2.

- ^ Anselin, Alain (2011). "Some notes about an Early African Pool of Cultures" in Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1-4073-0760-2.

- ^ Kivisild T, Reidla M, Metspalu E, Rosa A, Brehm A, Pennarun E, Parik J, Geberhiwot T, Usanga E, Villems R (2004). "Ethiopian Mitochondrial DNA Heritage: Tracking Gene Flow Across and Around the Gate of Tears". American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (5): 752–770. Bibcode:2004AmJHG..75..752K. doi:10.1086/425161. PMC 1182106. PMID 15457403.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David; Ehret, Christopher; A Brandt, Steven; Keita, Shomarka (9 June 2025). "Afrasian linguistics" in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology and Language (Mark Hudson, Martine Robbeets (eds) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 567–69. ISBN 978-0-19-269455-3.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David; Ehret, Christopher; A Brandt, Steven; Keita, Shomarka (9 June 2025). "Afrasian linguistics" in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology and Language (Mark Hudson, Martine Robbeets (eds) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 567–69. ISBN 978-0-19-269455-3.

- ^ Schoenbrun, David; Ehret, Christopher; A Brandt, Steven; Keita, Shomarka (9 June 2025). "Afrasian linguistics" in The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology and Language (Mark Hudson, Martine Robbeets (eds) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 567–69. ISBN 978-0-19-269455-3.

- ^ Oppenheim, Adela; Arnold, Dorothea; Arnold, Dieter; Yamamoto, Kei (12 October 2015). Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 307. ISBN 978-1-58839-564-1.

- ^ The Cambridge history of Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1975–1986. pp. 500–509. ISBN 978-0-521-22215-0.

- ^ The Oxford history of ancient Egypt (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2003. p. 479. ISBN 0-19-280458-8.

- ^ "It is important to note that historically not only was Upper Egypt the source of the core identifiable Egyptian culture, but that it was primarily southerners of the Eleventh/Twelfth, Seventeenth/Eighteenth, and Twenty-fifth Dynasties who politically reunited Egypt and reinvigorated its culture"Keita, S. O. Y. (September 2022). "Ideas about "Race" in Nile Valley Histories: A Consideration of "Racial" Paradigms in Recent Presentations on Nile Valley Africa, from "Black Pharaohs" to Mummy Genomest". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections.

- ^ Yurco, Frank J. (1989). Were the Ancient Egyptians Black Or White?. Biblical Archaeology Society.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka O. Y. (May 1981). "royal incest and diffusion in Africa". American Ethnologist. 8 (2): 392–393. doi:10.1525/ae.1981.8.2.02a00120.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka O. Y. (May 1981). "royal incest and diffusion in Africa". American Ethnologist. 8 (2): 392–393. doi:10.1525/ae.1981.8.2.02a00120.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (2023). Ancient Africa: a global history, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0691244099.

- ^ Williams, Bruce (1987). "Forebears of Menes in Nubia: Myth or Reality?". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 46 (1): 15–26. ISSN 0022-2968.

- ^ Williams, Bruce (1987). "Forebears of Menes in Nubia: Myth or Reality?". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 46 (1): 15–26. ISSN 0022-2968.

- ^ Williams, Bruce (1987). "Forebears of Menes in Nubia: Myth or Reality?". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 46 (1): 15–26. ISSN 0022-2968.

- ^ Davies, W. V. (1998). Egypt uncovered. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang. pp. 5–87. ISBN 1556708181.

- ^ Yurco, Frank J. (1996). "The Origin and Development of Ancient Nile Valley Writing". In Theodore Celenko (ed.). Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-936260-64-5.

- ^ Encyclopedia of precolonial Africa: archaeology, history, languages, cultures, and environments. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press. 1997. pp. 465–472. ISBN 0-7619-8902-1.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-691-24410-5.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 112-113. ISBN 978-0-691-24410-5.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-691-24410-5.

- ^ Anselin, Alain (2011). "Some notes about an Early African Pool of Cultures" in Egypt in its African context : proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1407307602.

- ^ Williams, Bruce (1996). "The Qustul Incense Bruner and the Case for a Nubian Origin of Ancient Egyptian Kingship" In Egypt in Africa. Celenko, Theodore (ed.). Indianapolis, Ind.: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-0936260648.

- ^ Darnell, John Coleman. "Rock Inscriptions and the Origin of Egyptian Writing" , in Abstracts of Papers Presented at the Third International Colloquium on Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt. London, British Museum Press (Edited by: McNamara, L, Friedman, R ed.). London, British Museum Press. pp. 82–3.

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan; Darnell, John Coleman; Gatto, Maria Carmela (December 2012). "The earliest representations of royal power in Egypt: the rock drawings of Nag el-Hamdulab (Aswan)". Antiquity. 86 (334): 1068–1083. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00048250. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 53631029.

- ^ Cultural Entanglement at the Dawn of the Egyptian History: A View From The Nile First Cataract Region; by Maria Carmela Gatto; 2014; published in Prehistory and Protohistory of Ancient Civilizations, from the Università Di Roma Dipartimento Di Scienze Dell'antichità – Museo Delle Origini; ISBN 978-88-492-3024-6, at [1]

- ^ Cultural Entanglement at the Dawn of the Egyptian History: A View From The Nile First Cataract Region; by Maria Carmela Gatto; 2014; published in Prehistory and Protohistory of Ancient Civilizations, from the Università Di Roma Dipartimento Di Scienze Dell'antichità – Museo Delle Origini; ISBN 978-88-492-3024-6, at [2]

- ^ Cultural Entanglement at the Dawn of the Egyptian History: A View From The Nile First Cataract Region; by Maria Carmela Gatto; 2014; published in Prehistory and Protohistory of Ancient Civilizations, from the Università Di Roma Dipartimento Di Scienze Dell'antichità – Museo Delle Origini; ISBN 978-88-492-3024-6, at [3]

- ^ Smith, Stuart Tyson (1 January 2018). "Gift of the Nile? Climate Change, the Origins of Egyptian Civilization and Its Interactions within Northeast Africa". Across the Mediterranean – Along the Nile: Studies in Egyptology, Nubiology and Late Antiquity Dedicated to László Török. Budapest.

- ^ Smith, Stuart Tyson (1 January 2018). "Gift of the Nile? Climate Change, the Origins of Egyptian Civilization and Its Interactions within Northeast Africa". Across the Mediterranean – Along the Nile: Studies in Egyptology, Nubiology and Late Antiquity Dedicated to László Török. Budapest.

- ^ Yurco, Frank J. (1996). "The Origin and Development of Ancient Nile Valley Writing". In Theodore Celenko (ed.). Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-936260-64-5.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. pp. 356–357.

- ^ Anselin, Alain (2011). "Some notes about an Early African Pool of Cultures" in Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1-4073-0760-2.

- ^ Anselin, Alain (2011). "Some notes about an Early African Pool of Cultures" in Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1-4073-0760-2.

- ^ Anselin, Alain (2011). "Some notes about an Early African Pool of Cultures" in Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1-4073-0760-2.

- ^ Anselin, Alain (2011). "Some notes about an Early African Pool of Cultures" in Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 43–54. ISBN 978-1-4073-0760-2.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (20 June 2023). Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Holl, Augustin. General history of Africa, IX: General history of Africa revisited. p. 533.

- ^ Rilly C (January 2016). "The Wadi Howar Diaspora and its role in the spread of East Sudanic languages from the fourth to the first millennia BCE". Faits de Langues. 47: 151–163. doi:10.1163/19589514-047-01-900000010. S2CID 134352296.

- ^ Cooper J (2017). "Toponymic Strata in Ancient Nubian placenames in the Third and Second Millennium BCE: a view from Egyptian Records". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4. Archived from the original on 2020-05-23.

- ^ Rilly, Claude (2019). "Languages of Ancient Nubia". Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-042038-8. Retrieved 2019-11-20. "Two Afro-Asiatic languages were present in antiquity in Nubia, namely Ancient Egyptian and Cushitic.

- ^ Bechhaus-Gerst, Marianne (27 January 2006). "Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan". In Blench, Roger; MacDonald, Kevin (eds.). The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography. Routledge. pp. 469–481. doi:10.4324/9780203984239-37 (inactive 1 July 2025). ISBN 978-1-135-43416-8.

}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Rice 1999, p. 86.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 57f.

- ^ Shaw 2000, p. 196.

- ^ a b Grajetzki (2006), pp. 109–111

General and cited references

[edit]- Ballais, Jean-Louis (2000). "Conquests and land degradation in the eastern Maghreb". In Graeme Barker; David Gilbertson (eds.). Sahara and Sahel. The Archaeology of Drylands: Living at the Margin. Vol. 1, Part III. London: Routledge. pp. 125–136. ISBN 978-0-415-23001-8.

- Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake, eds. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- Brice, William Charles (1981). An Historical Atlas of Islam. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-06116-9. OCLC 9194288.

- Chauveau, Michel (2000). Egypt in the Age of Cleopatra: History and Society Under the Ptolemies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3597-8.

- David, Ann Rosalie (1975). The Egyptian Kingdoms. London: Elsevier Phaidon. OCLC 2122106.

- Ermann, Johann Peter Adolf; Grapow, Hermann (1982). Wörterbuch der Ägyptischen Sprache [Dictionary of the Egyptian Language] (in German). Berlin: Akademie. ISBN 3-05-002263-9.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2006). The Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt: History, Archaeology and Society. London: Duckworth Egyptology. ISBN 978-0-7156-3435-6.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15449-9.

- Roebuck, Carl (1966). The World of Ancient Times. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons Publishing.

- Shaw, Ian (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18633-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Edel, Elmar (1961) Zu den Inschriften auf den Jahreszeitenreliefs der "Weltkammer" aus dem Sonnenheiligtum des Niuserre Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, OCLC 309958651, in German.

External links

[edit]- References to Upper Egypt in Coptic Literature—Coptic Scriptorium database