| William Clito | |

|---|---|

William's effigy on a seal | |

| Count of Flanders | |

| Reign | 2 March 1127 – 28 July 1128 |

| Predecessor | Charles I |

| Successor | Thierry |

| Born | 25 October 1102 Rouen, Caux, Normandy |

| Died | 28 July 1128 (aged 25) Aalst, Flanders |

| Burial | Abbey of Saint Bertin, Flanders |

| Spouse | |

| House | Normandy |

| Father | Robert Curthose |

| Mother | Sibylla of Conversano |

William Clito (25 October 1102 – 28 July 1128) was a member of the House of Normandy who ruled the County of Flanders from 1127 until his death and unsuccessfully claimed the Duchy of Normandy. As the son of Robert Curthose, the eldest son of William the Conqueror, William Clito was seen as a candidate to succeed his uncle King Henry I of England. Henry viewed him as a rival, however, and William allied himself with King Louis VI of France. Louis installed him as the new count of Flanders upon the assassination of Charles the Good, but the Flemings soon revolted and William died in the struggle against another claimant to Flanders, Thierry of Alsace.

Youth

[edit]William was the son of Duke Robert Curthose of Normandy and Sibylla of Conversano.[1] His father was the first son of King William the Conqueror of England. His nickname Clito was a Medieval Latin term equivalent to the Anglo-Saxon "Aetheling" and its Latinized form "Adelinus" (used to refer to his first cousin, William Adelin). Both terms signified "man of royal blood" or, the modern equivalent, "prince".[2] It may have been derived from the Latin inclitus/inclutus, "celebrated."[3]

Robert was defeated and captured by his brother King Henry I of England at the Battle of Tinchebrai in 1106.[4] Robert accompanied Henry to Falaise where Henry met his nephew William for the first time.[5] Henry placed his nephew in the custody of Helias of Saint Saens, count of Arques, who had married a natural daughter of Duke Robert, his friend and patron.[6] William stayed in his sister's and Helias's care until August 1110, when the king abruptly sent agents to demand the boy be handed over to him.[7] Helias was at the time away from home, so his household concealed William and smuggled him to their master, who fled the duchy and found safety among Henry's enemies.[7]

Claimant to the English Crown

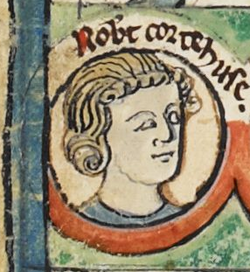

[edit] Robert Curthose, William's father, as depicted on folio 5r of British Library Royal 14 B VI.[8]

Robert Curthose, William's father, as depicted on folio 5r of British Library Royal 14 B VI.[8]

William's first refuge was with King Henry's great enemy, Robert de Bellême, who had extensive estates south of the duchy.[9] On Robert's capture in 1112, William and Helias fled to the court of the young Count Baldwin VII of Flanders, William's cousin. Baldwin formed an alliance with Louis VI of France and Fulk of Anjou, and fighting began in earnest by 1118.[10]

The Norman border counts and Count Baldwin between them were too powerful for the king and seized much of the north of the duchy. Baldwin's offensive specifically was taking place in the county of Talou, also known as Arques.[11] The campaign in northeastern Normandy ended in September 1118 with the mortal wounding of Baldwin, who was then attacking Arques-la-Bataille, which damaged Clito's cause severely.[12][13] Baldwin died on 17 June 1119 and his successor, Charles, ended the conflict with Henry.[12]

The next year the cause of William Clito was taken up by King Louis VI of France. He raided the duchy down the river Seine, and seized the castle of Les Andelys, which he used as a base.[14] Henry won many of the Norman barons to his side during Lent of 1119, but there were also fresh betrayals, and the loyalty of the Norman baronage continued to erode on the whole.[15] During the same time, Henry granted Alençon to Stephen of Blois, so that he could assist in its defence.[15] Stephen's misrule led to his loss of the castle before the end of 1118.[16] Henry won a diplomatic victory when in June 1119 he married his only legitimate son William Adelin to Fulk, who then went on crusade to Jerusalem, where he would become king.[17]

Louis VI, accompanied by William as a young knight, launched an offensive from Les Andelys through the Norman Vexin to capture Noyon-sur-Andelle. About the same time, Henry was progressing southwards from Noyon, and neither was aware of the latter's presence. Thus, the ensuing Battle of Brémule was an accident.[18] The French acted carelessly in the battle and were decisively defeated, with Henry taking many noble prisoners.[19] Louis, who escaped alongside Clito, attempted a failed counterattack, and the active fighting between Henry and Louis ended for the most part. The Baronial revolt also fizzled out.[20]

William continued to find support at the French court. Louis brought his case to the pope's attention in October 1119 at Reims, but Henry successfully justified his treatment of the boy.[21] William attempted to negotiate with Henry for his father's release, but was merely offered money. Angrily, he refused, and though Henry had the opportunity to arrest him, he did not.[22]

The White Ship

[edit]Henry finally embarked for England on 25 November 1120.[22] Henry allowed his son William Adelin, as well as his illegitimate son Richard, and they were joined by much of the younger Anglo-Norman nobility. The port side of the White Ship crashed upon a rock, capsizing the entire vessel, and sending many of the passengers to their deaths, alongside William and Richard. Henry lost both his only legitimate son, and the dynastic security he came with.[23]

The event transformed William Clito's fortunes.[24] At the state of events after the White Ship, William was the most plausible heir to the English throne.[25] He was now 18, popular, healthy, and a military veteran of multiple campaigns.[26] William was known as a young man of significant martial prowess, charm, and charisma.[27][28]

Henry's problems became worse, as William Adelin had been betrothed to Matilda, daughter of Count Fulk V of Anjou, and Fulk demanded the return of her dowry of several castles and towns in the county of Maine, between Normandy and Anjou. Henry refused.[24] Fulk, in turn, betrothed his daughter Sibylla to William Clito, giving to him the entire county of Maine as her dowry.[24] King Henry appealed astutely to canon law, however, and the marriage was eventually annulled in August 1124 on the grounds that the couple were within the prohibited degree of kinship.[29] Henry finally named a new heir by 1126–his daughter Empress Matilda–and had the barons swear on oath of loyalty to her in January 1127.[26]

In the meantime, a serious aristocratic rebellion broke out in Normandy in favour of William, primarily led by Amaury de Montfort but was defeated by Henry's intelligence network and the lack of organisation of the leaders, who were defeated at the Battle of Bourgthéroulde in March 1124.[30] Amaury's revolt included many young members of the Norman aristocracy, including Waleran of Meulan.[31] Louis VI was distracted from active intervention as Henry I persuaded his son-in-law Emperor Henry V to threaten Louis from the east.[32]

Still, after this great effort, William enjoyed substantial support from the Anglo-Norman nobility to succeed Henry.[33] In January of 1127, Louis married Clito to his wife's half-sister, Jeanne (or Joanna) of Montferrat.[34] He then granted William the castles of the French Vexin, including Mantes.[35][26]

Count of Flanders

[edit] The murder of Charles the Good, from the Grandes Chroniques de France

The murder of Charles the Good, from the Grandes Chroniques de France

Charles of Flanders, was murdered on 2 March 1127 by the Erembalds, who opposed his attempts to curb their power.[36] A struggle took place over the course of the year to establish William as count, and with Louis' support, William was elected on 2 March 1127.[37][38] The new count faced a total of 4 separate claimants for Flanders.[39] Henry rallied Baldwin, Count of Hainault, his father-in-law Godfrey, Duke of Lower Lorraine, and Flemish internal claimants against Clito.[40] Allies of William including Hugh III, Count of Saint-Pol and Walter of Vladslo besieged Aire, which was loyal to William of Ypres, and captured it.[41] By the end of April, William Clito, alongside the king, had capture William of Ypres.[42] By May of 1127, William was temporarily without effective challengers for Flanders.[43]

A 20th-century crucifix monument that mentions the Battle of Axspoele

A 20th-century crucifix monument that mentions the Battle of Axspoele

Henry immediately challenged William's claim to Flanders, and ordered Stephen of Blois to invade.[44] Stephen's attack was unsuccessful and William's counterattack into Boulogne forced him into a three-year truce.[45][44] At this time, William also established Helias of Saint-Saëns as lord of Montreuil.[45] Henry damaged his position by enacting a wool sanction against Flanders, financially supporting enemy claimants, and claiming Flanders himself.[44] This, coupled with William's exactions against the Flemish towns, led to a general revolt that left him without most of his county.[46]

Thierry of Alsace yet another claimant, arose by April of 1128.[47] William vigorously counterattacked in the next few months, which began to throw Thierry on the defensive.[48] On the 18th and 19th of Bruges, Thierry gathered a large army from the Flemish towns and besieged the estate of Axspoele, held by an ally of William's, though had been being watched by Clito.[49] At the Battle of Axspoele, William led Thierry's vanguard into an ambush and then routed his army.[50][48] At this point, William was joined by Count Godfrey I of Louvain, and together their armies besieged Aalst on 12 July, with the probable intention of going on from there to reduce Ghent. The citizens of Bruges feared that William would exact harsh repercussions.[51]

During the course of the siege he was wounded in the arm in a scuffle with a foot soldier. The wound became gangrenous and William died at the age of twenty-five on 28 July 1128, attended to the end by his faithful brother-in-law, Helias of Saint-Saëns, whose wife was one of William's illegitimate half-sisters. William had written letters to Henry I asking for his followers to be pardoned; Henry did as requested. Some followers returned to Henry I while others set out for the crusade.[52] William's body was carried to the abbey of Saint Bertin in St. Omer and buried there. He left no children and was survived by his imprisoned father by six years.

References

[edit]- ^ Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue Folge, Band II (Verlag von J. A. Stargardt, Marburg, Germany, 1984), Tafel 81.

- ^ Clemoes, Peter; Biddle, Martin; Brown, Julian; Derolez, René (11 October 2007). Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521038652 – via Google Books.

- ^ Aird, William M. (28 September 2011). Robert 'Curthose', Duke of Normandy (C. 1050-1134). Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843836605 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 675.

- ^ C. Warren Hollister, Henry I (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2003), pp. 204-6.

- ^ C. Warren Hollister, Henry I (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2003), p. 206.

- ^ a b David Crouch, The Normans; The History of a Dynasty (Hambledon Continuum, New York, 2007), p. 185.

- ^ Royal MS 14 B VI (n.d.).

- ^ Kathleen Thompson, 'Robert of Bellême Reconsidered', Anglo-Norman Studies XIII; Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1990, Ed. Marjorie Chibnall (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 1991), p. 278.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 247.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 249.

- ^ a b Hollister 2003, p. 251.

- ^ Aird 2008, p. 257.

- ^ Aird 2008, pp. 260–261.

- ^ a b Hollister 2003, p. 250.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 252.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 261.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 263.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 264.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 266.

- ^ Aird 2008, pp. 264–268.

- ^ a b Aird 2008, p. 268.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 277.

- ^ a b c Sandy Burton Hicks, 'The Anglo-Papal Bargain of 1125: The Legatine Mission of John of Crema', Albion, Vol. 8, No. 4, (Winter, 1976), p. 302.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 280.

- ^ a b c Andrews, J. F. (8 January 2021). Lost Heirs of the Medieval Crown: The Kings and Queens Who Never Were. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-5267-3652-9.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 312.

- ^ Aird 2008, p. 255, 271.

- ^ Edward Augustus Freeman, The History of the Norman Conquest of England, Its Causes and Its Results, Vol V (Oxford, at the Clarendon Press, 1876), p. 199.

- ^ Aird 2008, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 292.

- ^ Halphen 1926, p. 604.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 313.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 318.

- ^ Aird 2003, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Aird 2008, p. 271.

- ^ Aird 2008, p. 272.

- ^ Tanner 2004, p. 183.

- ^ Tanner 2004, p. 184.

- ^ Hicks 1981, p. 43–44.

- ^ Galbert Of Bruges (1967). The Murder Of Charles The Good. Harper Torchbooks, London.

- ^ Tanner 2004, p. 185.

- ^ Hicks 1981, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Hollister 2003, p. 320.

- ^ a b Tanner 2004, p. 186.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 272.

- ^ Hollister 2003, p. 321.

- ^ a b Schenk 2019, p. 48.

- ^ Verbruggen 1977, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Verbruggen 1977, pp. 208–210.

- ^ Schenk 2019, p. 49.

- ^ C. Warren Hollister, Henry I (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2003), p. 325.

Further reading

[edit]- Galbert of Bruges, The Murder of Charles the Good, trans. J.B. Ross (repr. Toronto, 1982)

- Sandy Burton Hicks, "The Impact of William Clito upon the Continental Policies of Henry I of England," Viator 10 (1979), 1–21.

- J. A. Green, Henry I (Cambridge, 2006)

- Aird, William M. (2008). Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy C. 1050 –1134. Boydell Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-84383-310-9.

- Hollister, C. Warren (2003). Henry I. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14372-0.

- Tanner, Heather (1 February 2004). Families, Friends and Allies: Boulogne and Politics in Northern France and England, c.879-1160. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-474-0255-8.

- Verbruggen, J. F. (1977). The art of warfare in Western Europe during the Middle Ages : from the eighth century to 1340. Internet Archive. Amsterdam ; New York : North-Holland Pub. Co. ; New York : distributors for the U.S.A. and Canada, Elsevier/North Holland. ISBN 978-0-7204-9006-0.