This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2011) |

An 1879 illustration of a praxinoscope

An 1879 illustration of a praxinoscope

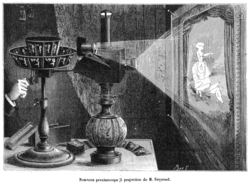

A projecting praxinoscope, 1882

A projecting praxinoscope, 1882

The Théâtre Optique, 1892. This ultimate elaboration of the device used long strips with hundreds of narrative images.

The Théâtre Optique, 1892. This ultimate elaboration of the device used long strips with hundreds of narrative images.

The praxinoscope is an animation device, the successor to the zoetrope. It was invented in France in 1877 by Charles-Émile Reynaud. Like the zoetrope, it uses a strip of pictures placed around the inner surface of a spinning cylinder. The praxinoscope improved on the zoetrope by replacing its narrow viewing slits with an inner circle of mirrors,[1] placed so that the reflections of the pictures appeared more or less stationary in position as the wheel turned. Someone looking in the mirrors can, therefore, see a rapid succession of images producing the illusion of motion, with a brighter and less distorted picture than the zoetrope offered.

Precedents

[edit]The author of the first retinal resistance theory was Joseph Plateau, who, in 1832 invented the first Phenakistiscope which consisted of a cardboard disk which’s perimeter was holed by equidistant radiants that carried the drawings that represented the different phases of a circular motion. If the eye was disposed at the same height as the hole was during the fast circular motion of the disk, it created the illusion of movement.[2]

Almost at the same time, Simon Stamper invented the Stroboscope, which was only differentiated by the separation of the holes and the drawings made from two different disks which rotated in different directions.[3]

Finally, the most famous invention, previous to the creation of the first Praxinoscope, was the zoetrope, developed by William George Horner in 1834. [4] The holes in this invention were on top of the black cylinder, and the drawings were disposed thorough a non-removable tape on the interior of the invention.[5]

Nevertheless, the greatest inconvenience these inventions had was the lost of light caused by the holes, a problem that would persist until the use of mirrors on future inventions which would help to increase the clarity of the projections.

Variations

[edit]Reynaud introduced the Praxinoscope-Théâtre in 1879. This was basically the same device, but it was hidden inside a box to show only the moving figures within added theatrical scenery. When the set was assembled inside the unfolded box, the viewer looked through a rectangular slot in the front, onto a plate with a transparent mirror surrounded by a printed proscenium. The mirror reflected a background and a floor that were printed on interchangeable cards placed on the inside of the folded lid of the box, below the viewing slot. The animated figures were printed on black strips, so they were all that was visible through the transparent mirror and appeared to be moving within the suggested space that was reflected from the background and floor cards. The set appeared with 20 strips (all based on previous standard praxinoscope strips), 12 backgrounds and a mirror intended for background effects for the swimming figure. This set also sold very well and appeared in slight variations, including a deluxe version made of thuja-wood with ebony inlays.[6]

Reynaud mentioned the possibility of projecting the images in his 1877 patent. He presented a praxinoscope projection device at the Société française de photographie on 4 June 1880, but did not market his praxinoscope a projection before 1882. Only a handful of examples are known to still exist.[7]

In 1888 Reynaud developed the Théâtre Optique, an improved version capable of projecting images on a screen from a longer roll of pictures. From 1892 he used the system for his Pantomimes lumineuses: a show with hand-drawn animated stories for larger audiences. It was very successful for several years, until it was eclipsed in popularity by the photographic film projector of the Lumière brothers.

The kinematofor made by Ernst Plank, of Nuremberg, Germany: a variation of the praxinoscope, powered by a miniature hot air engine.

The kinematofor made by Ernst Plank, of Nuremberg, Germany: a variation of the praxinoscope, powered by a miniature hot air engine.

The praxinoscope was copied by several other companies. Ernst Plank offered several variations, including one that was automated by a small hot air engine.

Movement of a Praxinoscope

[edit]The movement a praxinoscope developes, consists of a sequence of movements where the same action is repeated all over again in a circular motion, just to activate and deactivate the mechanism of the object. [8] In this kind of optical inventions, the way the object is perceived and how it is manipulated becomes a crucial part of the process. The eye of the spectator should become static so that the movement can happen right how it should. This movement is regulated by the person who activates the sequence.

Simple Harmonic motion

[edit]This movement describes a force which is proportional to the distant the images are travelling. The movement generates a repetition every specific time period. This movement will only be considered Simple Harmonic motion if the force that generates the movement is proportional to the distance travelled by the images.

Uniform circular motion

[edit]The uniform circular motion represents the movement an object makes, maintaining a constant speed in a circular motion.[9] There are two speeds to consider: the velocity of the movement of the object, and the speed in which the turning angle varies. Even though the speed of an object may be constant, its velocity may not: velocity is a vectorial magnitude, tangent to the trajectory, which means in every instant it changes direction.[10]

20th century revival

[edit]The Red Raven Magic Mirror and its special children's phonograph records, introduced in the US in 1956, was a 20th-century adaptation of the praxinoscope. The Magic Mirror was a sixteen-sided praxinoscopic reflector with angled facets. It was placed over the record player's spindle and rotated along with the 78 rpm record, which had a very large label with a sequence of sixteen interwoven animation frames arrayed around its center. As the record played, the user gazed into the Magic Mirror and saw an endlessly repeating animated scene that illustrated the recorded song. In the 1960s, versions of the Red Raven system were introduced in Europe and Japan under various names—Teddy in France and the Netherlands, Mamil Moviton in Italy, etc.[11][12]

Etymology

[edit]The word praxinoscope translates roughly as "action viewer", from the Greek roots πραξι- (confer πρᾶξις "action") and scop- (confer σκοπός "watcher").

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brunn, Stanley D.; Cutter, Susan L.; Harrington, J.W. Jr. (31 March 2004). Geography and technology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 274. ISBN 978-1402018718.

- ^ "A very short history of cinema | National Science and Media Museum". National Science and Media Museum. Archived from the original on 2025-09-25. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ "Fenaquistoscopio | Museo del Cine". museudelcinema.girona.cat. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ "Phenakistoscopes (1833)". The Public Domain Review. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ "Optical Toys". Museum of the Moving Image. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ Mannoni 1995

- ^ Laurent Mannoni, The great art of light and shadow : archaeology of the cinema (1995)

- ^ "Les 10 ans du Conservatoire des techniques, trois anniversaires, hommage à deux pionniers : Émile Reynaud et Georges Demenÿ. Conférence de Sylvie Saerens et Laurent Mannoni - La Cinémathèque française". www.cinematheque.fr. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ "Circular Motion and Rotation". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ "Physics Tutorial: Motion of a Mass on a Spring". www.physicsclassroom.com. Retrieved 2025-12-17.

- ^ Retro Thing: Red Raven Animated Records (includes two animated GIF images of typical animations)

- ^ Digging For Gold, Part 1 (Blog entry, shows the early cardboard-based type of Red Raven record and a rare variant of the Magic Mirror)