| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

Jewish cosmology refers to the cosmological views articulated in Jewish through through modern and premodern times. Jewish cosmology adopted, but also built on, biblical cosmology, blending it with other influences, from observation, ancient Near Eastern cosmology, Ancient Greek astronomy, and more. There is no definitive cosmological model that mechanically explains how the world works according to Judaism, with massive collections of writings like the Talmud presenting differing and competing views and models across the range of sages and rabbinic authorities.

Jewish cosmology can be found in biblical literature, noncanonical literature from the period of Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE), rabbinic literature, para-rabbinic literature (notably including Pirkei De-Rabbi Eliezer), and more.

By text

[edit]Book of Enoch

[edit]Early Jewish apocalyptic literature appeared around the same time as the earliest systematic thinking about the origins and structure of the cosmos.[1] The earliest examples of this can be found in two texts compiled later into the Book of Enoch: the Astronomical Book (1 Enoch 72–82) and the Book of the Watchers (1 Enoch 1–36). These two books were both later compiled into a single document, the Book of Enoch. In chapter 72, the Astronomical Book discusses the path of the sun. Chapters 73 and 74 discuss the path of the moon, and 75 with that of the stars. In its 77th chapter, the Earth is divided into four parts: north, south, east, and west. A second, three-fold division of the Earth based on the function of the Earth areas is also given: first, the region inhabited by humans, second, the region inhabited by other creatures (the sea, forests, and so on), and third, the "garden of righteousness" (gannata ṣedq). Finally, at the edge of the earth there are seven great mountains, rivers, and islands, all of which are bigger than any of their counterparts within Earth's circumscribed area.[2]

The Book of Watchers focuses on the aspects of the cosmos that are experienced by humans in cycles, particularly the paths of the sun, moon, stars, the seasons, the motions of seas and rivers, etc. However, man has corrupted the world by turning its elements into weapons and performing divination on the astral bodies. In order to respond to this, humans can make pleas to the archangels who sit at the gates of heaven, who in turn, will petition God to carry out punishments and purifications.[3]

The heavenly gates, which offer passageways for the sun and moon to pass through the heavenly firmament, are largely described in the Astronomical Book. In total, there are twelve sun-moon gates: six in the east for rising every morning and six in the west for setting. These gates form six pairs between east and west: each of the six eastern gates have a directly opposite gate in the west, and if the sun rises from a specific eastern gate, it will set in its corresponding western gate. The sun consecutively passes through each of the six gate-pairs 30 or 31 times in a row (corresponding to a month), and it does this for each pair of gates twice per year, with the total Enochic calendar adding up to 364 days. The need for all these gates may have arisen because human observers saw that the sun does not always rise and set from the exact same eastern and western points in the sky every day. The celestial journey of the sun was assisted by a chariot carrying it and a push from favorable winds (which, in 1 Enoch, also explains the movements of the stars). The daily journey of the sun is complete when it enters the corresponding western gate as it sets. The moon uses the same gates as the sun, and it also uses the suns light. 1 Enoch also has gates for where the major winds come from, divided into favorable winds and unfavorable winds for humans. To explain where the elements and luminaries go when they exit through gates, 1 Enoch has large storehouses. There are four types: storehouses for winds, for thunder and lightning, for water and rain, and for the luminaries.[4][5]

The Book of Watchers helps narrate the geography of the heavens as it describes the ascent into the heavens by Enoch, a process that takes him to the three-tiered heavenly palace (which resembles the Temple in Jerusalem), and where he receives assistance from clouds, shooting stars, and other natural forces. During his ascent, Enoch finds the 'storehouses of all the winds': these windows are forces which support the earth and firmament, move the astral bodies in their paths, and expand the skies.[6] He also reaches the largest (and throne-shaped) of the seven mountains where God himself is said to take seat. Later in the tour, he finds a mountain at the 'center of the earth' (26:1).[7]

3 Baruch

[edit]3 Baruch has a bipartite involving heaven and earth without mention of an underworld. Aside from Jerusalemite topography and a list of rivers, no geographic description of earth is offered. The water circle that integrates the heavenly and earthly waters is, however, an important concern for this text. An uncrossable river, Oceanus, separates heaven and earth and is filled by the earths rivers from one side while bring drunk from by beasts on the others. Terrestrial rivers, in turn, are supplied by heavenly waterfall (like rain and dew). The "foundation of heaven", the firmament, is heavens lowermost support. The lowermost bounds also makes contact with the uppermost ends of the earth, similar to 1 Enoch's reference that Enoch saw "the ends of earth whereon heaven rests, and the portals of the heaven open" (31:1-2). In later rabbinic literature, this is described as heaven and earth coming to "kiss each other". In 3 Baruch, they meet at the Oceanus, due to the vaulted or hemispherical nature of the firmament: the lower ends of heaven meet the earth. There are 365 gates or celestial windows at the firmament through which the sun passes when it rises and sets.[8] According to later rabbinic cosmography, there were 182 gates in the east, 182 in the west, and one in the center through which the sun passed right after the creation period. The need for one gate for the sun to pass through per day emerges from the revolution of heaven in relation to earth.[9] Such gates may be contextualized into those mentioned in the writings of Homer and other texts from early Greek cosmology and ancient near eastern cosmology.[10] Unique to the uranology of 3 Baruch is that the final stage of the ascent to heaven terminates at the fifth heaven, with no others mentioned as existing beyond.[11]

Rabbinic literature

[edit]Rabbinic cosmology represents a synthesis of ancient near eastern cosmology, early Greek cosmology, and biblical cosmology, framed into the sensibilities of contemporary Jewish thought and morality. These include statements describing Oceanus encircling the earth, statements of the earth being like a plate with the heaven (firmament) as a cover, and that the earth sits upon a cosmic body of water. The firmament is held up by pillars, and furthermore, the sky represents a series of layered firmaments. Distances between each of the heavens, measured by the number of years that could be traversed during human journey, were speculated.[12]

In rabbinic literature, the idea of seven heavens constituting the cosmos became the norm, although occasionally even greater numbers are found, such as in the ten heavens of 2 Enoch.[13][14]

Peter Schafer has called b. Hagiga 12b–13a the locus classicus of rabbinic cosmology; this passage offers law on what constitutes prohibited sexual relationships, the works of creation (maʿase bereshit), and discusses the "chariot" of Ezekiel 1. It is in the maʿase bereshit where cosmological commentary becomes important. The passage outlines what constitutes acceptable inquiry regarding cosmology, discusses the size of the first man, describes ten things created on the first day (heaven and earth, tohu and bohu, light and darkness, wind and water, and the measure of day and of night). In part, this lists responds to the notion that some of these elements (like darkness) were uncreated and primordial already when God began creating. Then, ten of God's attributes during creation are listed (one being rebuke, because God would for example expand the cosmos until he "rebuked" or "shouted" at it). Discussion moves onto the Earth with the exposition of Genesis 1:2, where the detail about pillars of the Earth is assimilated from Job 9:6.[15] The seven heavens are discussed and their names are stated ("(1) Welon, (2) Raqia‘, (3) Shehaqim, (4) Zevul, (5) Ma‘on, (6) Makhon, (7) ‘Aravot") and each is described. For example, the second heaven contains the stars and constellation, along with the sun and the moon. The sixth heaven, Makhon, contains only unpleasant things like rain and storms. The seventh and highest heaven contains only that which is good. The description of the heavens is mid-way interrupted by dicta from two rabbis about the rewards of studying the Torah. The closest parallel to the structure of the cosmos outlined in this passage is found later, in the Seder Rabba di-Bereshit and in Re’uyot Yehezqel.[16]

A place where the wicked are punished is assumed, without being explicitly mentioned, in the Talmud. An elaborate geographic description of this type of place is found in the Seder Rabba di-Bereshit.[17]

The Talmud

[edit]Talmudic cosmology, as preserved in rabbinic discussions from late antiquity, presents a view of cosmology reflecting a variety of individual sages, instead of a single definitive model. The Earth is generally conceived as flat and stationary, resting upon pillars, and ultimately, on the sustaining power of God, with variant opinions ranging from there being one to twelve pillars. Above the Earth lies the rakia (firmament): an opaque, solid structure that separates the terrestrial realm from the heavens and is itself composed, according to some sages, of seven distinct layers. The sun is believed to travel beneath the rakia during the day and either above it or beneath the Earth at night, an event that has practical legal consequences for ritual observance. The rabbis recognized the sun, moon, and the five planets as distinct celestial bodies, under the umbrella of terms like kohavim and mazzalot. Talmudic cosmology was distinct from Ptolemaic astronomy. It depended on a combination of biblical exegesis, observation, inherited imagery from ancient Near Eastern cosmology, and limited Greco-Roman scientific influence.[18]

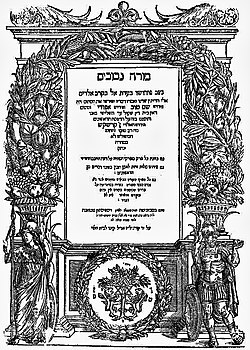

Maimonides

[edit]Maimonides (1138–1204) articulated the most systematic cosmology in medieval Jewish thought, adopting a clearly Ptolemaic, geocentric model of the universe while simultaneously criticizing the philosophical foundations it rested on. In his legal code, the Mishneh Torah, he describes a universe composed of concentric, transparent celestial spheres surrounding a stationary Earth, beginning with the sphere of the moon and extending outward through the planets, the fixed stars, and a ninth sphere that is responsible for daily motion. Maimonides' model incorporated both epicycles and other complex celestial motions derived from Ancient Greek astronomy, which, in his time, was taken as the normative scientific framework. Despite this, However, in his The Guide for the Perplexed, he articulated Aristotelian objections to Ptolemaic astronomy, questioning the plausibility of epicycles and differing celestial velocities, and emphasizing the limited nature to which confidence could be assigned to scientific knowledge. Though Maimonides maintained that the Earth was immobile, he also explicitly rejected the idea that astronomical models could be taken as articles of faith, and he allowed for the possibility that both rabbinic and philosophical authorities could be wrong in matters of natural science, paving the way for acceptance of new scientific discoveries in Jewish thought in future centuries.[19]

Firmament

[edit]A distinctive collection of ideas about the cosmos were drawn up and recorded in the rabbinic literature, though the conception is rooted deeply in the tradition of near eastern cosmology recorded in Hebrew, Akkadian, and Sumerian sources, combined with some additional influences in the newer Greek ideas about the structure of the cosmos and the heavens in particular.[20] The rabbis viewed the heavens to be a solid object spread over the Earth, which was described with the biblical Hebrew word for the firmament, raki’a. Two images were used to describe it: either as a dome, or as a tent; the latter inspired from biblical references, though the latter is without an evident precedent.[21] As for its composition, just as in cuneiform literature the rabbinic texts describe that the firmament was made out of a solid form of water, not just the conventional liquid water known on the Earth. A different tradition makes an analogy between the creation of the firmament and the curdling of milk into cheese. Another tradition is that a combination of fire and water makes up the heavens. This is somewhat similar to a view attributed to Anaximander, whereby the firmament is made of a mixture of hot and cold (or fire and moisture).[22] Yet another dispute concerned how thick the firmament was. A view attributed to R. Joshua b. R. Nehemiah was that it was extremely thin, no thicker than two or three fingers. Some rabbis compared it to a leaf. On the other hand, some rabbis viewed it as immensely thick. Estimates that it was as thick as a 50 year journey or a 500 year journey were made. Debates on the thickness of the firmament also impacted debates on the path of the sun in its journey as it passes through the firmament through passageways called the "doors" or "windows" of heaven.[23] The number of heavens or firmaments was often given as more than one: sometimes two, but much more commonly, seven. It is unclear whether the notion of the seven heavens is related to earlier near eastern cosmology or the Greek notion of the surrounding of the Earth by seven concentric spheres: one for the sun, one for the moon, and one for each of the five other (known) planets.[24] A range of additional discussions in rabbinic texts surrounding the firmament included those on the upper waters,[25] the movements of the heavenly bodies and the phenomena of precipitation,[26] and more.[27][28]

The firmament also appears in non-rabbinic Jewish literature, such as in the cosmogonic views represented in the apocrypha. A prominent example is in the Book of Enoch composed around 300 BC. In this text, the sun rises from one of six gates from the east. It crosses the sky and sets into a window through the firmament in the west. The sun then travels behind the firmament back to the other end of the Earth, from whence it could rise again.[29] In the Testament of Solomon, the heavens are conceived in a tripartite structure and demons are portrayed as being capable of flying up to and past the firmament in order to eavesdrop on the decisions of God.[30] Another example of Jewish literature describing the firmament can be found in Samaritan poetry.[31]

Heavenly bodies

[edit]Imaginative commentary on the sun and moon are found in multiple texts, including in the Book of Enoch and 3 Baruch, where, for example, the sun and moon are respectively personified as a man and a woman riding their own chariots drawn by angels.[32]

Paradise

[edit]Paradise is located in one of the heavens in Jewish cosmology. Different texts may place it in different locations: for example, it is to be found on the third heaven in the Book of Enoch but in the fourth heaven in 3 Baruch.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Schafer 2005, p. 39.

- ^ Reed 2016, p. 74–75.

- ^ Reed 2016, p. 77–78.

- ^ Dubovsky 2000.

- ^ Ratzon 2015.

- ^ Reed 2016, p. 79–81.

- ^ Reed 2016, p. 82–83.

- ^ Kulik 2019, p. 240–242.

- ^ Kulik 2019, p. 244.

- ^ Kulik 2019, p. 242–243.

- ^ Kulik 2019, p. 246–248.

- ^ Safrai 2006, p. 506–508.

- ^ Schafer 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Kulik 2019, p. 252–264.

- ^ Schafer 2005, p. 40–42.

- ^ Schafer 2005, p. 42–51.

- ^ a b Schafer 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Brown 2013, p. 27–34.

- ^ Brown 2013, p. 34–38.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 72.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 72–75.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 75–77.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 77–80.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 80–81.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 81–88.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 88–96.

- ^ Hannam 2023, p. 150–151.

- ^ Hannam 2023, p. 149.

- ^ Brannon 2011, p. 196.

- ^ Lieber 2022, p. 137–138.

- ^ Schafer 2005, p. 51–52.

Sources

[edit]- Brannon, M. Jeff (2011). The Heavenlies in Ephesians: A Lexical, Exegetical, and Conceptual Analysis. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Brown, Jeremy (2013). "The Talmudic View of the Universe". New Heavens and a New Earth: The Jewish Reception of Copernican Thought. Oxford University Press. pp. 27–41.

- Dubovsky, Peter (2000). "Cosmology in 1 Enoch". Archiv Orientalni: Quarterly Journal of African and Asian Studies. 68: 205–218.

- Hannam, James (2023). The Globe: How the Earth became Round. Reaktion Books.

- Kulik, Alexander (2019). "The enigma of the five heavens and early Jewish cosmology". Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha. 28 (4): 239–266. doi:10.1177/0951820719861900.

- Lieber, Laura Suzanne (2022). Classical Samaritan Poetry. Eisenbrauns.

- Ratzon, Eshbal (2015). "The Gates Cosmology of the Astronomical Book of Enoch". Dead Sea Discoveries. 22 (1): 93–111.

- Reed, Annette Y. (2016). Burnett, Charles; Kraye, Jill (eds.). Enoch, Eden, and the Beginnings of Jewish Cosmography. Warburg Institute Colloquia. pp. 67–94.

- Safrai, Zeev (2006). "Geography and Cosmography in Talmudic Literature". In Safrai z'l, Shmuel; Safrai, Ze'ev; Schwartz, Joshua J.; Tomson, Peter (eds.). The Literature of the Jewish People in the Period of the Second Temple and the Talmud, Volume 3: The Literature of the Sages. Brill. pp. 497–508.

- Schafer, Peter (2005). "From Cosmology to Theology: The Rabbinic Appropriation of Apocalyptic Cosmology". In Elior, Rachel; Schafer, Peter (eds.). Creation and Re-Creation in Jewish Thought: Festschrift in Honor of Joseph Dan on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 39–58.

- Simon-Shoshan, Moshe (2008). ""The Heavens Proclaim the Glory of God..." A Study in Rabbinic Cosmology" (PDF). Bekhol Derakhekha Daehu–Journal of Torah and Scholarship. 20: 67–96.

Further reading

[edit]- Reed, Annette Yoshiko (2009). ""Who Can Recount the Mighty Acts of the Lord?": Cosmology and Authority in "Pirqei deRabbi Eliezer" 1—3". Hebrew Union College Annual. 80: 115–141. JSTOR 23509782.

- Reed, Annette Yoshiko (2014). "2 Enoch and the Trajectories of Jewish Cosmology: From Mesopotamian Astronomy to Greco-Egyptian Philosophy in Roman Egypt". The Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy. 22 (1): 1–24.

- Schafer, Peter (2004). "In Heaven as It Is in Hell: The Cosmology of Seder Rabba di-Bereshit". In Boustan, Ra’anan S.; Reed, Annette Yoshiko (eds.). Heavenly Realms and Earthly Realities in Late Antique Religions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 233–274.

- Wright, Edward J. (2000). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press.