A black hole is an astronomical body so compact that its gravity prevents anything, including light, from escaping. Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass will form a black hole.[4] The boundary of no escape is called the event horizon. In general relativity, a black hole's event horizon seals an object's fate but produces no locally detectable change when crossed.[5] General relativity also predicts that every black hole should have a central singularity, where the curvature of spacetime is infinite.

In many ways, a black hole acts like an ideal black body, as it reflects no light.[6][7] Quantum field theory in curved spacetime predicts that event horizons emit Hawking radiation, with the same spectrum as a black body of a temperature inversely proportional to its mass. This temperature is of the order of billionths of a kelvin for stellar black holes, making it essentially impossible to observe directly.

Objects whose gravitational fields are too strong for light to escape were first considered in the 18th century by John Michell and Pierre-Simon Laplace. In 1916, Karl Schwarzschild found the first modern solution of general relativity that would characterise a black hole. Due to his influential research, the Schwarzschild metric is named after him. David Finkelstein, in 1958, first interpreted Schwarzschild's model as a region of space from which nothing can escape. Black holes were long considered a mathematical curiosity; it was not until the 1960s that theoretical work showed they were a generic prediction of general relativity. The first black hole known was Cygnus X-1, identified by several researchers independently in 1971.[8][9]

Black holes typically form when massive stars collapse at the end of their life cycle. After a black hole has formed, it can grow by absorbing mass from its surroundings. Supermassive black holes of millions of solar masses may form by absorbing other stars and merging with other black holes, or via direct collapse of gas clouds. There is consensus that supermassive black holes exist in the centres of most galaxies.

The presence of a black hole can be inferred through its interaction with other matter and with electromagnetic radiation such as visible light. Matter falling toward a black hole can form an accretion disk of infalling plasma, heated by friction and emitting light. In extreme cases, this creates a quasar, some of the brightest objects in the universe. Merging black holes can also be detected by observation of the gravitational waves they emit. If other stars are orbiting a black hole, their orbits can be used to determine the black hole's mass and location. Such observations can be used to exclude possible alternatives such as neutron stars. In this way, astronomers have identified numerous stellar black hole candidates in binary systems and established that the radio source known as Sagittarius A*, at the core of the Milky Way galaxy, contains a supermassive black hole of about 4.3 million solar masses.

History

[edit]The idea of a body so massive that even light could not escape was briefly proposed by English astronomical pioneer and clergyman John Michell and independently by French scientist Pierre-Simon Laplace. Both scholars proposed very large stars in contrast to the modern concept of an extremely dense object.[10]

Michell's idea, in a short part of a letter published in 1784,[11] calculated that a star with the same density but 500 times the radius of the sun would not let any emitted light escape; the surface escape velocity would exceed the speed of light.[12]: 122 Michell correctly noted that such supermassive but non-radiating bodies might be detectable through their gravitational effects on nearby visible bodies.[10]

In 1796, Laplace mentioned that a star could be invisible if it were sufficiently large while speculating on the origin of the Solar System in his book Exposition du Système du Monde. Franz Xaver von Zach asked Laplace for a mathematical analysis, which Laplace provided and published in a journal edited by von Zach.[10] Laplace omitted his comment about invisible stars in later editions of his book, perhaps because Thomas Young's wave theory of light had cast doubt on the validity of the corpuscles of light used in Laplace's mathematical analysis.[12]: 123

General relativity

[edit]| General relativity |

|---|

|

In 1905 Albert Einstein showed that the laws of electromagnetism would be invariant under a Lorentz transformation: they would be identical for observers travelling at different velocities relative to each other. This discovery became known as the principle of special relativity. Although the laws of mechanics had already been shown to be invariant, gravity remained yet to be included.[13]: 19

To add gravity to the his theory of relativity, Einstein was guided by observations by Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton and others which showed inertial mass equalled gravitational mass.[13]: 11 In 1907, Einstein published a paper proposing his equivalence principle, the hypothesis that this equality means the two forms of mass have a common cause. Using the principle, Einstein predicted the redshift effect of gravity on light.[13]: 19 In 1911, Einstein predicted[14] the deflection of light by massive bodies, but his analysis was premature and off by a factor of two.[13]: 19

By 1917, Einstein refined these ideas into his general theory of relativity, which explained how matter affects spacetime, which in turn affects the motion of other matter.[15][16][17] This theory formed the basis for black hole physics.[18]

Singular solutions in general relativity

[edit]Only a few months after Einstein published the field equations describing general relativity, astrophysicist Karl Schwarzschild set out to apply the idea to stars. He assumed spherical symmetry with no spin and found a solution to Einstein's equations.[12]: 124 [19] A few months after Schwarzschild, Johannes Droste, a student of Hendrik Lorentz, independently gave the same solution for the point mass using a different set of coordinates.[20][21] At a certain radius from the center of the mass, the Schwarzschild solution became singular, meaning that some of the terms in the Einstein equations became infinite. The nature of this radius, which later became known as the Schwarzschild radius, was not understood at the time.[22]

Many physicists of the early 20th century were skeptical of the existence of black holes. In a 1926 popular science book, Arthur Eddington discussed the idea of a star with mass compressed to its Schwarzschild radius, but his analysis was meant to illustrate issues in the then-poorly-understood theory of general relativity rather than to seriously analyze the problem: Eddington did not believe black holes existed.[23][12]: 134 In 1939, Einstein himself used his theory of general relativity in an attempt to prove that black holes were impossible.[24][25] His work relied on increasing pressure or increasing centrifugal force balancing the force of gravity so that the object would not collapse beyond its Schwarzschild radius. He missed the possibility that implosion would drive the system below this critical value.[12]: 135

Gravity vs degeneracy pressure

[edit]By the 1920s, astronomers had classified a number of white dwarf stars as too cool and dense to be explained by the gradual cooling of ordinary stars. In 1926, Ralph Fowler showed that quantum-mechanical degeneracy pressure was larger than thermal pressure at these densities.[12]: 145 In 1931, using a combination of special relativity and quantum mechanics, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar calculated that a non-rotating body of electron-degenerate matter below a certain limiting mass (now called the Chandrasekhar limit at 1.4 M☉) is stable, and by 1934 he showed that this explained the catalog of white dwarf stars.[12]: 151 At the same meeting where Chandrasekhar announced his results, Eddington pointed out that stars above this limit would radiate until they were sufficiently dense to prevent light from exiting, a conclusion he considered absurd. Eddington and, later, Lev Landau argued that some yet unknown mechanism would stop the collapse.[26] They were partially correct: a white dwarf slightly more massive than the Chandrasekhar limit will collapse into a neutron star, which is itself stable.[27] These arguments from senior scientists delayed acceptance of Chandrasekhar's model.[12]: 159

In the 1930s, Fritz Zwicky and Walter Baade studied stellar novae, focusing on exceptionally bright ones they called supernovae. Zwicky promoted the idea that supernovae produced stars with the density of atomic nuclei—neutron stars—but this idea was largely ignored.[12]: 171 In 1937, Lev Landau published a detailed model of a nuclear core model for stellar cores, which caught the attention of Robert Oppenheimer. In 1939, based on Chandrasekhar's reasoning, Oppenheimer and George Volkoff predicted that neutron stars below a certain mass limit—now known as the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit—would be stable due to neutron degeneracy pressure. Above that limit, they reasoned that either their model would not apply or that gravitational contraction would not stop.[28]: 380

John Archibald Wheeler and two of his students resolved questions about the model behind the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) limit. Harrison and Wheeler developed the equations of state relating density to pressure for cold matter all the way from atoms through electron degeneracy to neutron degeneracy. Masami Wakano and Wheeler then used the equations to compute the equilibrium curve for stars, relating mass to circumference. They found no additional features that would invalidate the TOV limit. This meant that the only thing that could prevent black holes from forming was a dynamic process ejecting sufficient mass from a star as it cooled.[12]: 205 Wheeler held the view that the neutrons in an imploding star would convert to electromagnetic radiation fast enough that the resulting light would not be trapped in a black hole.[12]: 210

Birth of modern model

[edit]The modern concept of black holes was formulated by Robert Oppenheimer and his student Hartland Snyder in 1939.[24][29]: 80 In the paper,[30] Oppenheimer and Snyder solved Einstein's equations of general relativity for an idealized imploding star, in a model later called the Oppenheimer–Snyder model, then described the results from far outside the star. The implosion starts as one might expect: the star material rapidly collapses inward. But as density of the star increases, gravitational time dilation increases and the collapse, viewed from afar, seems to slow down. Once the star reached a critical radius—its Schwarzschild radius—faraway viewers would no longer see the implosion. The light from the implosion would be infinitely redshifted and time dilation would be so extreme that it would appear frozen in time.[12]: 217

In 1958, David Finkelstein identified the Schwarzschild surface as an event horizon, calling it "a perfect unidirectional membrane: causal influences can cross it in only one direction". In this sense, events that occur inside of the black hole cannot affect events that occur outside of the black hole.[31] Finkelstein created a new reference frame to include the point of view of infalling observers.[29]: 103 Finkelstein's solution extended the Schwarzschild solution for the future of observers falling into a black hole. A similar concept had already been found by Martin Kruskal, but its significance had not been fully understood at the time.[29]: 103 Finkelstein's new frame of reference allowed events at the event horizon of an imploding star to be related to events far away. By 1962 the two points of view were reconciled, convincing many skeptics that implosion into a black hole made physical sense.[12]: 226

Golden age

[edit] The first simulated image of a black hole, created by Jean-Pierre Luminet in 1978 and featuring the characteristic shadow, photon sphere, and lensed accretion disk. The disk is brighter on one side due to the Doppler beaming.[32][33]

The first simulated image of a black hole, created by Jean-Pierre Luminet in 1978 and featuring the characteristic shadow, photon sphere, and lensed accretion disk. The disk is brighter on one side due to the Doppler beaming.[32][33]

The era from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s was the "golden age of black hole research", when general relativity and black holes became mainstream subjects of research.[34][12]: 258

In this period, more general black hole solutions were found. In 1963, Roy Kerr found the exact solution for a rotating black hole.[35][36] Two years later, Ezra Newman found the cylindrically symmetric solution for a black hole that is both rotating and electrically charged.[37]

In 1967, Werner Israel found that the Schwarzschild solution was the only possible solution for a nonspinning, uncharged black hole, and couldn't have any additional parameters. In that sense, a Schwarzschild black hole would be defined by its mass alone, and any two Schwarzschild black holes with the same mass would be identical.[38] Israel later found that Reissner-Nordstrom black holes were only defined by their mass and electric charge, while Brandon Carter discovered that Kerr black holes only had two degrees of freedom, mass and spin.[39][40] Together, these findings became known as the no-hair theorem, which states that a stationary black hole is completely described by the three parameters of the Kerr–Newman metric: mass, angular momentum, and electric charge.[41]

At first, it was suspected that the strange mathematical singularities found in each of the black hole solutions only appeared due to the assumption that a black hole would be perfectly spherically symmetric, and therefore the singularities would not appear in generic situations where black holes would not necessarily be symmetric. This view was held in particular by Vladimir Belinski, Isaak Khalatnikov, and Evgeny Lifshitz, who tried to prove that no singularities appear in generic solutions, although they would later reverse their positions.[42] However, in 1965, Roger Penrose proved that general relativity without quantum mechanics requires that singularities appear in all black holes.[43][44] Shortly afterwards, Hawking generalized Penrose's solution to find that in all but a few physically infeasible scenarios, a cosmological Big Bang singularity is inevitable unless quantum gravity intervenes.[45]

Astronomical observations also made great strides during this era. In 1967, Antony Hewish and Jocelyn Bell Burnell discovered pulsars[46][47] and by 1969, these were shown to be rapidly rotating neutron stars.[48] Until that time, neutron stars, like black holes, were regarded as just theoretical curiosities, but the discovery of pulsars showed their physical relevance and spurred a further interest in all types of compact objects that might be formed by gravitational collapse.[49] Based on observations in Greenwich and Toronto in the early 1970s, Cygnus X-1, a galactic X-ray source discovered in 1964, became the first astronomical object commonly accepted to be a black hole.[50][51]

Work by James Bardeen, Jacob Bekenstein, Carter, and Hawking in the early 1970s led to the formulation of black hole thermodynamics.[52] These laws describe the behaviour of a black hole in close analogy to the laws of thermodynamics by relating mass to energy, area to entropy, and surface gravity to temperature. The analogy was completed[12]: 442 when Hawking, in 1974, showed that quantum field theory implies that black holes should radiate like a black body with a temperature proportional to the surface gravity of the black hole, predicting the effect now known as Hawking radiation.[53]

Modern research and observation

[edit]The first strong evidence for black holes came from combined X-ray and optical observations of Cygnus X-1 in 1972.[54] The x-ray source, located in the Cygnus constellation, was discovered through a survey by two suborbital rockets, as the blocking of x-rays by Earth's atmosphere makes it difficult to detect them from the ground.[55][56][57] Unlike stars or pulsars, Cygnus X-1 was not associated with any prominent radio or optical source.[57][58] In 1972, Louise Webster, Paul Murdin, and, independently, Charles Thomas Bolton, found that Cygnus X-1 was actually in a binary system with the supergiant star HDE 226868. Using the emission patterns of the visible star, both research teams found that the mass of Cygnus X-1 was likely too large to be a white dwarf or neutron star, indicating that it was probably a black hole.[59][60] Further research strengthened their hypothesis.[61][62]

While Cygnus X-1, a stellar-mass black hole, was generally accepted by the scientific community as a black hole by the end of 1973,[61] it would be decades before a supermassive black hole would gain the same broad recognition. Although, as early as the 1960s, physicists such as Donald Lynden-Bell and Martin Rees had suggested that powerful quasars in the center of galaxies were powered by accreting supermassive black holes, little observational proof existed at the time.[63][64] However, the Hubble Space Telescope, launched decades later, found that supermassive black holes were not only present in these active galactic nuclei, but that supermassive black holes in the center of galaxies were ubiquitous: Almost every galaxy had a supermassive black hole at its center, many of which were quiescent.[65][66]

In 1999, David Merritt proposed the M–sigma relation, which related the dispersion of the velocity of matter in the center bulge of a galaxy to the mass of the supermassive black hole at its core.[67] Subsequent studies confirmed this correlation.[68][69][70] Around the same time, based on telescope observations of the velocities of stars at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, independent work groups led by Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel concluded that the compact radio source in the center of the galaxy, Sagittarius A*, was likely a supermassive black hole.[71][72]

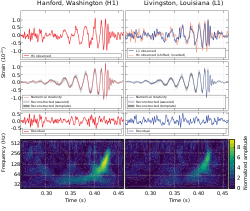

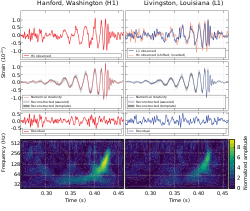

The first detection of gravitational waves, imaged by LIGO observatories in Hanford Site, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana

The first detection of gravitational waves, imaged by LIGO observatories in Hanford Site, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana

On 11 February 2016, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration announced the first direct detection of gravitational waves, named GW150914, representing the first observation of a black hole merger.[73] At the time of the merger, the black holes were approximately 1.4 billion light-years away from Earth and had masses of 30 and 35 solar masses.[74]: 6 The mass of the resulting black hole was approximately 62 solar masses, with an additional three solar masses radiated away as gravitational waves.[74][75] The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detected the gravitational waves by using two mirrors spaced four kilometers apart to measure microscopic changes in length.[76] In 2017, Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne, and Barry Barish, who had spearheaded the project, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their work.[77] Since the initial discovery in 2015, hundreds more gravitational waves have been observed by LIGO and another interferometer, Virgo.[78]

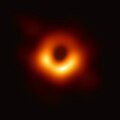

Image by the Event Horizon Telescope of the supermassive black hole in the center of Messier 87

Image by the Event Horizon Telescope of the supermassive black hole in the center of Messier 87

On 10 April 2019, the first direct image of a black hole and its vicinity was published, following observations made by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) in 2017 of the supermassive black hole in Messier 87's galactic centre.[79][80][81] The observations were carried out by eight observatories in six geographical locations across four days and totaled five petabytes of data.[82][83][84] In 2022, the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration released an image of the black hole in the center of the Milky Way galaxy, Sagittarius A*; The data had been collected in 2017.[85] Detailed analysis of the motion of stars recorded by the Gaia mission produced evidence in 2022[86] and 2023[87] of a black hole named Gaia BH1 in a binary with a Sun-like star about 1,560 light-years (480 parsecs) away. Gaia BH1 is currently the closest known black hole to Earth.[88][89] Two more black holes have since been found from Gaia data, one in a binary with a red giant[90] and the other in a binary with a G-type star.[91]

In 2020, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded for work on black holes. Andrea Ghez and Reinhard Genzel shared one-half for their discovery that Sagittarius A* is a supermassive black hole.[92] Penrose received the other half for his work showing that the mathematics of general relativity requires the formation of black holes.[93][94][95] Cosmologists lamented that Hawking's extensive theoretical work on black holes would not be honored since he died in 2018.[96]

Etymology

[edit]In December 1967, a student reportedly suggested the phrase black hole at a lecture by John Wheeler; Wheeler adopted the term for its brevity and "advertising value", and Wheeler's stature in the field ensured it quickly caught on,[29][97] leading some to credit Wheeler with coining the phrase.[98]

However, the term was used by others around that time. Science writer Marcia Bartusiak traces the term black hole to physicist Robert H. Dicke, who in the early 1960s reportedly compared the phenomenon to the Black Hole of Calcutta, notorious as a prison where people entered but never left alive. The term was used in print by Life and Science News magazines in 1963, and by science journalist Ann Ewing in her article "'Black Holes' in Space", dated 18 January 1964, which was a report on a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science held in Cleveland, Ohio.[29]

Definition

[edit]A black hole is generally defined as a region of spacetime from which no information-carrying signals or objects can escape.[99] However, verifying an object as a black hole by this definition would require waiting for an infinite time and at an infinite distance from the black hole to verify that indeed, nothing has escaped, and thus cannot be used to identify a physical black hole.[100] Broadly, physicists do not have a precisely-agreed-upon definition of a black hole. Among astrophysicists, a black hole is a compact object with a mass larger than four solar masses.[101] A black hole may also be defined as a reservoir of information[102]: 142 or a region where space is falling inwards faster than the speed of light.[103][104]

Properties

[edit]The no-hair theorem postulates that, once it achieves a stable condition after formation, a black hole has only three independent physical properties: mass, electric charge, and angular momentum; the black hole is otherwise featureless. If the conjecture is true, any two black holes that share the same values for these properties, or parameters, are indistinguishable from one another. The degree to which the conjecture is true for real black holes is currently an unsolved problem.[41]

The simplest static black holes have mass but neither electric charge nor angular momentum. These black holes are often referred to as Schwarzschild black holes after Karl Schwarzschild, who discovered the solution in 1916.[19] According to Birkhoff's theorem, it is the only vacuum solution that is spherically symmetric.[105] Solutions describing more general black holes also exist. Non-rotating charged black holes are described by the Reissner–Nordström metric, while the Kerr metric describes a non-charged rotating black hole. The most general stationary black hole solution known is the Kerr–Newman metric, which describes a black hole with both charge and angular momentum.[106]

Mass

[edit]The simplest static black holes have mass but neither electric charge nor angular momentum. Contrary to the popular notion of a black hole "sucking in everything" in its surroundings, from far away, the external gravitational field of a black hole is identical to that of any other body of the same mass.[107]

While a black hole can theoretically have any positive mass, the charge and angular momentum are constrained by the mass. The total electric charge Q and the total angular momentum J are expected to satisfy the inequality for a black hole of mass M. Black holes with the maximum possible charge or spin satisfying this inequality are called extremal black holes. Solutions of Einstein's equations that violate this inequality exist, but they do not possess an event horizon. These are so-called naked singularities that can be observed from the outside.[108] Because these singularities make the universe inherently unpredictable, many physicists believe they could not exist.[109] The weak cosmic censorship hypothesis, proposed by Sir Roger Penrose, rules out the formation of such singularities, when they are created through the gravitational collapse of realistic matter. However, this theory has not yet been proven, and some physicists believe that naked singularities could exist.[110] It is also unknown whether black holes could even become extremal, forming naked singularities, since natural processes counteract increasing spin and charge when a black hole becomes near-extremal.[110][111][112]

The total mass of a black hole can be estimated by analyzing the motion of objects near the black hole, such as stars or gas.[66]

Spin and angular momentum

[edit]All black holes spin, often fast—One supermassive black hole, GRS 1915+105 has been estimated to spin at over 1,000 revolutions per second.[113][114] The Milky Way's central black hole Sagittarius A* rotates at about 90% of the maximum rate.[115][116]

The spin rate can be inferred from measurements of atomic spectral lines in the X-ray range. As gas near the black hole plunges inward, high energy X-ray emission from electron-positron pairs illuminates the gas further out, appearing red-shifted due to relativistic effects. Depending on the spin of the black hole, this plunge happens at different radii from the hole, with different degrees of redshift. Astronomers can use the gap between the x-ray emission of the outer disk and the redshifted emission from plunging material to determine the spin of the black hole.[117]

A newer way to estimate spin is based on the temperature of gasses accreting onto the black hole. The method requires an independent measurement of the black hole mass and inclination angle of the accretion disk followed by computer modeling. Gravitational waves from coalescing binary black holes can also provide the spin of both progenitor black holes and the merged hole, but such events are rare.[117]

A spinning black hole has angular momentum. The supermassive black hole in the center of the Messier 87 (M87) galaxy appears to have an angular momentum very close to the maximum theoretical value.[115][118][119] That uncharged limit is [120] allowing definition of a dimensionless spin magnitude such that[120][121]

Charge

[edit]Most black holes are believed to have an approximately neutral charge. For example, Michal Zajaček, Arman Tursunov, Andreas Eckart, and Silke Britzen found the electric charge of Sagittarius A* to be at least ten orders of magnitude below the theoretical maximum.[122] A charged black hole repels other like charges just like any other charged object.[123] If a black hole were to become charged, particles with an opposite sign of charge would be pulled in by the extra electromagnetic force, while particles with the same sign of charge would be repelled, neutralizing the black hole. This effect may not be as strong if the black hole is also spinning.[124] The presence of charge can reduce the diameter of the black hole by up to 38%.[122][125]

The charge Q for a nonspinning black hole is bounded by where G is the gravitational constant and M is the black hole's mass.[126]

Classification

[edit]| Class | Approx. mass |

Approx. radius |

|---|---|---|

| Ultramassive black hole | 109–1011 M☉ | >1,000 AU |

| Supermassive black hole | 106–109 M☉ | 0.001–400 AU |

| Intermediate-mass black hole[127] | 102–105 M☉ | 103 km ≈ REarth |

| Stellar black hole | 2–150 M☉ | 30 km |

| Micro black hole | up to MMoon | up to 0.1 mm |

Black holes can have a wide range of masses. The minimum mass of a black hole formed by stellar gravitational collapse is governed by the maximum mass of a neutron star and is believed to be approximately two-to-four solar masses.[128][129][130] However, theoretical primordial black holes, believed to have formed soon after the Big Bang, could be far smaller, with masses as little as 10−5 grams at formation.[131] These very small black holes are sometimes called micro black holes.[132][133]

Black holes formed by stellar collapse are called stellar black holes. Estimates of their maximum mass at formation vary, but generally range from 10 to 100 solar masses, with higher estimates for black holes progenated by low-metallicity stars.[134] The mass of a black hole formed via a supernova has a lower bound: If the progenitor star is too small, the collapse may be stopped by the degeneracy pressure of the star's constituents, allowing the condensation of matter into an exotic denser state. Degeneracy pressure occurs from the Pauli exclusion principle—Particles will resist being in the same place as each other. Smaller progenitor stars, with masses less than about 8 M☉, will be held together by the degeneracy pressure of electrons and will become a white dwarf. For more massive progenitor stars, electron degeneracy pressure is no longer strong enough to resist the force of gravity and the star will be held together by neutron degeneracy pressure, which can occur at much higher densities, forming a neutron star. If the star is still too massive, even neutron degeneracy pressure will not be able to resist the force of gravity and the star will collapse into a black hole.[135][136]: 5.8 Stellar black holes can also gain mass via accretion of nearby matter, often from a companion object such as a star.[137][138][139]

Black holes that are larger than stellar black holes but smaller than supermassive black holes are called intermediate-mass black holes, with masses of approximately 102 to 105 solar masses. These black holes seem to be rarer than their stellar and supermassive counterparts, with relatively few candidates having been observed.[140][127][141] Physicists have speculated that such black holes may form from collisions in globular and star clusters or at the center of low-mass galaxies.[142][143][144][145][146] They may also form as the result of mergers of smaller black holes, with several LIGO observations finding merged black holes within the 110-350 solar mass range.[147][148]

The black holes with the largest masses are called supermassive black holes, with masses more than 106 times that of the Sun.[140][149][150] These black holes are believed to exist at the centers of almost every large galaxy, including the Milky Way.[65][66][151][152] Some scholars have theorized that the collapse of very massive population III stars in the early universe could have produced black holes of up to 103 M☉. These black holes could be the seeds of the supermassive black holes found in the centres of most galaxies.[153] Some scientists have proposed a subcategory of even larger black holes, called ultramassive black holes, with masses greater than 109-1010 solar masses.[154][155][156] Theoretical models predict that the accretion disc that feeds black holes will be unstable once a black hole reaches 50-100 billion times the mass of the Sun, setting a rough upper limit to black hole mass.[157][158]

Structure

[edit] An artistic depiction of a black hole and its features

An artistic depiction of a black hole and its features

While black holes are conceptually invisible sinks of all matter and light, in astronomical settings, their enormous gravity alters the motion of surrounding objects and pulls nearby gas inwards at near-light speed, making the area around black holes the brightest objects in the universe.[159]

External geometry

[edit]Relativistic jets

[edit] Relativistic jets from the supermassive black hole in Centaurus A extend perpendicularly from the galaxy.

Relativistic jets from the supermassive black hole in Centaurus A extend perpendicularly from the galaxy.

Some black holes have relativistic jets—thin streams of plasma travelling away from the black hole at more than one-tenth of the speed of light.[160] A small faction of the matter falling towards the black hole gets accelerated away along the hole rotation axis.[161] These jets can extend as far as millions of parsecs from the black hole itself.[162]

Black holes of any mass can have jets.[163] However, they are typically observed around spinning black holes with strongly-magnetized accretion disks.[164][165] Relativistic jets were more common in the early universe, when galaxies and their corresponding supermassive black holes were rapidly gaining mass.[164][166] All black holes with jets also have an accretion disk, but the jets are usually brighter than the disk.[160][167] Quasars, typically found in other galaxies, are believed to be supermassive black holes with jets; microquasars are believed to be stellar-mass objects with jets, typically observed in the Milky Way.[168]

The mechanism of formation of jets is not yet known,[163] but several options have been proposed. One method proposed to fuel these jets is the Blandford-Znajek process, which suggests that the dragging of magnetic field lines by a black hole's rotation could launch jets of matter into space.[169][170] The Penrose process, which involves extraction of a black hole's rotational energy, has also been proposed as a potential mechanism of jet propulsion.[171][172]

Accretion disk

[edit] Visualization of a black hole with an orange accretion disk. The parts of the disk circling over and under the hole are actually gravitationally lensed from the back side of the black hole.[173][174]

Visualization of a black hole with an orange accretion disk. The parts of the disk circling over and under the hole are actually gravitationally lensed from the back side of the black hole.[173][174]

Due to conservation of angular momentum, gas falling into the gravitational well created by a massive object will typically form a disk-like structure around the object.[175]: 242 As the disk's angular momentum is transferred outward due to internal processes, its matter falls farther inward, converting its gravitational energy into heat and releasing a large flux of x-rays.[176][177][178][179] The temperature of these disks can range from thousands to millions of Kelvin, and temperatures can differ throughout a single accretion disk.[180][181] Accretion disks can also emit in other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, depending on the disk's turbulence and magnetization and the black hole's mass and angular momentum.[179][182][183]

Accretion disks can be defined as geometrically thin or geometrically thick. Geometrically thin disks are mostly confined to the black hole's equatorial plane and have a well-defined edge at the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO), while geometrically thick disks are supported by internal pressure and temperature and can extend inside the ISCO. Disks with high rates of electron scattering and absorption, appearing bright and opaque, are called optically thick; optically thin disks are more translucent and produce fainter images when viewed from afar.[184] Accretion disks of black holes accreting beyond the Eddington limit are often referred to as polish donuts due to their thick, toroidal shape that resembles that of a donut.[185][186][187]

Quasar accretion disks are expected to usually appear blue in color.[188] The disk for a stellar black hole, on the other hand, would likely look orange, yellow, or red, with its inner regions being the brightest.[189] Theoretical research suggests that the hotter a disk is, the bluer it should be, although this is not always supported by observations of real astronomical objects.[190] Accretion disk colors may also be altered by the Doppler effect, with the part of the disk travelling towards an observer appearing bluer and brighter and the part of the disk travelling away from the observer appearing redder and dimmer.[191][192][193]

Innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO)

[edit] Since particles in a black hole's accretion disk must orbit at or outside the ISCO, astronomers can observe the properties of accretion disks to determine black hole spins.[194]

Since particles in a black hole's accretion disk must orbit at or outside the ISCO, astronomers can observe the properties of accretion disks to determine black hole spins.[194]

In Newtonian gravity, test particles can stably orbit at arbitrary distances from a central object. In general relativity, however, there exists a smallest possible radius for which a massive particle can orbit stably. Any infinitesimal inward perturbations to this orbit will lead to the particle spiraling into the black hole, and any outward perturbations will, depending on the energy, cause the particle to spiral in, move to a stable orbit further from the black hole, or escape to infinity. This orbit is called the innermost stable circular orbit, or ISCO.[195][196] The location of the ISCO depends on the spin of the black hole and the spin of the particle itself. In the case of a Schwarzschild black hole (spin zero) and a particle without spin, the location of the ISCO is: where is the radius of the ISCO, is the Schwarzschild radius of the black hole, is the gravitational constant, and is the speed of light.[197] The radius of this orbit changes slightly based on particle spin.[198][199] For charged black holes, the ISCO moves inwards.[198] For spinning black holes, the ISCO is moved inwards for particles orbiting in the same direction that the black hole is spinning (prograde) and outwards for particles orbiting in the opposite direction (retrograde).[196] For example, the ISCO for a particle orbiting retrograde can be as far out as about , while the ISCO for a particle orbiting prograde can be as close as at the event horizon itself.[196][200]

Photon sphere and shadow

[edit]Video of a photon being captured by a Schwarzschild black hole

The photon sphere is a spherical boundary for which photons moving on tangents to that sphere are bent completely around the black hole, possibly orbiting multiple times.[201] Light rays with impact parameters less than the radius of the photon sphere enter the black hole.[202] For Schwarzschild black holes, the photon sphere has a radius 1.5 times the Schwarzschild radius; the radius for non-Schwarzschild black holes is at least 1.5 times the radius of the event horizon.[203][204] When viewed from a great distance, the photon sphere creates an observable black hole shadow.[203] Since no light emerges from within the black hole, this shadow is the limit for possible observations.[205]: 152 The shadow of colliding black holes should have characteristic warped shapes, allowing scientists to detect black holes that are about to merge.[206]

While light can still escape from the photon sphere, any light that crosses the photon sphere on an inbound trajectory will be captured by the black hole. Therefore, any light that reaches an outside observer from the photon sphere must have been emitted by objects between the photon sphere and the event horizon.[206] Light emitted towards the photon sphere may also curve around the black hole and return to the emitter.[207]

For a rotating, uncharged black hole, the radius of the photon sphere depends on the spin parameter and whether the photon is orbiting prograde or retrograde.[197] For a photon orbiting prograde, the photon sphere will be 1-3 Schwarzschild radii from the center of the black hole, while for a photon orbiting retrograde, the photon sphere will be between 3-5 Schwarzschild radii from the center of the black hole. The exact location of the photon sphere depends on the magnitude of the black hole's rotation.[208] For a charged, nonrotating black hole, there will only be one photon sphere, and the radius of the photon sphere will decrease for increasing black hole charge.[209] For non-extremal, charged, rotating black holes, there will always be two photon spheres, with the exact radii depending on the parameters of the black hole.[210]

Ergosphere

[edit] The ergosphere is a region outside of the event horizon, where objects cannot remain in place.[211]

The ergosphere is a region outside of the event horizon, where objects cannot remain in place.[211]

Near a rotating black hole, spacetime rotates similar to a vortex. The rotating spacetime will drag any matter and light into rotation around the spinning black hole. This effect of general relativity, called frame dragging, gets stronger closer to the spinning mass. The region of spacetime in which it is impossible to stay still is called the ergosphere.[212]

The ergosphere of a black hole is a volume bounded by the black hole's event horizon and the ergosurface, which coincides with the event horizon at the poles but bulges out from it around the equator.[211]

Matter and radiation can escape from the ergosphere. Through the Penrose process, objects can emerge from the ergosphere with more energy than they entered with. The extra energy is taken from the rotational energy of the black hole, slowing down the rotation of the black hole.[213]: 268 A variation of the Penrose process in the presence of strong magnetic fields, the Blandford–Znajek process, is considered a likely mechanism for the enormous luminosity and relativistic jets of quasars and other active galactic nuclei.[169][214]

Plunging region

[edit]The observable region of spacetime around a black hole closest to its event horizon is called the plunging region. In this area it is no longer possible for free falling matter to follow circular orbits or stop a final descent into the black hole. Instead, it will rapidly plunge toward the black hole at close to the speed of light, growing increasingly hot and producing a characteristic, detectable thermal emission.[215][216][217] However, light and radiation emitted from this region can still escape from the black hole's gravitational pull.[218]

Radius

[edit]For a nonspinning, uncharged black hole, the radius of the event horizon, or Schwarzschild radius, is proportional to the mass, M, through where rs is the Schwarzschild radius and M☉ is the mass of the Sun.[219]: 124 For a black hole with nonzero spin or electric charge, the radius is smaller,[Note 1] until an extremal black hole could have an event horizon close to half the radius of a nonspinning, uncharged black hole of the same mass.[220]

Event horizon

[edit]The defining feature of a black hole is the existence of an event horizon, a boundary in spacetime through which matter and light can pass only inward towards the center of the black hole. Nothing, not even light, can escape from inside the event horizon.[221][222] The event horizon is referred to as such because if an event occurs within the boundary, information from that event cannot reach or affect an outside observer, making it impossible to determine whether such an event occurred.[223]: 179 For non-rotating black holes, the geometry of the event horizon is precisely spherical, while for rotating black holes, the event horizon is oblate.[224][225]

To a distant observer, a clock near a black hole would appear to tick more slowly than one further from the black hole.[136]: 217 This effect, known as gravitational time dilation, would also cause an object falling into a black hole to appear to slow as it approached the event horizon, never quite reaching the horizon from the perspective of an outside observer.[136]: 218 All processes on this object would appear to slow down, and any light emitted by the object to appear redder and dimmer, an effect known as gravitational redshift.[226] An object falling from 1/2 of a Schwarzschild radius above the event horizon would fade away until it could no longer be seen, disappearing from view within one hundredth of a second.[227] It would also appear to flatten onto the black hole, joining all other material that had ever fallen into the hole.[228]

On the other hand, an observer falling into a black hole would not notice any of these effects as they cross the event horizon. Their own clocks appear to them to tick normally, and they cross the event horizon after a finite time without noting any singular behaviour. In general relativity, it is impossible to determine the location of the event horizon from local observations, due to Einstein's equivalence principle.[136]: 222 [229]

Internal geometry

[edit]Cauchy horizon

[edit]Black holes that are rotating and/or charged have an inner horizon, often called the Cauchy horizon, inside of the black hole.[230][231] The inner horizon is divided up into two segments: an ingoing section and an outgoing section.[232]

At the ingoing section of the Cauchy horizon, radiation and matter that fall into the black hole would build up at the horizon, causing the curvature of spacetime to go to infinity. This would cause an observer falling in to experience tidal forces.[230][231][232] This phenomenon is often called mass inflation, since it is associated with a parameter dictating the black hole's internal mass growing exponentially,[231][233] and the buildup of tidal forces is called the mass-inflation singularity[234][232] or Cauchy horizon singularity.[235][236] Some physicists have argued that in realistic black holes, accretion and Hawking radiation would stop mass inflation from occurring.[237][238]

At the outgoing section of the inner horizon, infalling radiation would backscatter off of the black hole's spacetime curvature and travel outward, building up at the outgoing Cauchy horizon. This would cause an infalling observer to experience a gravitational shock wave and tidal forces as the spacetime curvature at the horizon grew to infinity. This buildup of tidal forces is called the shock singularity.[233][232]

Both of these singularities are weak, meaning that an object crossing them would only be deformed a finite amount by tidal forces, even though the spacetime curvature would still be infinite at the singularity. This is as opposed to a strong singularity, where an object hitting the singularity would be stretched and squeezed by an infinite amount.[230][234][233] They are also null singularities, meaning that a photon could travel parallel to the them without ever being intercepted.[232]

Singularity

[edit]Mathematical models of black holes based on general relativities have singularities at their centers—points where the curvature of spacetime becomes infinite, and geodesics terminate within a finite proper time. However, it is unknown whether these singularities truly exist in real black holes.[239] Some physicists believe that singularities do not exist, and that their existence, which would make spacetime unpredictable, signals a breakdown of general relativity and a need for a more complete understanding of quantum gravity.[240][241][242] Others believe that such singularities could be resolved within the current framework of physics, without having to introduce quantum gravity.[239] There are also physicists, including Kip Thorne[191] and Charles Misner,[243] who believe that not all singularities can be resolved, and that some likely still exist in the real universe despite the effects of quantum gravity.[239][244] Finally, still others believe that singularities do not exist, and that their existence in general relativity does not matter, since general relativity is already believed to be an incomplete theory.[239]

According to general relativity, every black hole has a singularity inside.[136]: 205 [245] For a non-rotating black hole, this region takes the shape of a single point; for a rotating black hole it is smeared out to form a ring singularity that lies in the plane of rotation.[136]: 264 In both cases, the singular region has zero volume. All of the mass of the black hole ends up in the singularity.[136]: 252 Since the singularity has nonzero mass in an infinitely small space, it can be thought of as having infinite density.[246]

Chaotic oscillations of spacetime experienced by an object approaching a gravitational singularityObservers falling into a Schwarzschild black hole (i.e., non-rotating and not charged) cannot avoid being carried into the singularity once they cross the event horizon.[247][248] As they fall further into the black hole, they will be torn apart by the growing tidal forces in a process sometimes referred to as spaghettification or the noodle effect. Eventually, they will reach the singularity and be crushed into an infinitely small point.[223]: 182

Before the 1970s, most physicists believed that the interior of a Schwarzschild black hole curved inwards towards a sharp point at the singularity. However, in the late 1960s, Soviet physicists Vladimir Belinskii, Isaak Khalatnikov, and Evgeny Lifshitz discovered that this model was only true when the spacetime inside the black hole had not been perturbed. Any perturbations, such as those caused by matter or radiation falling in, would cause space to oscillate chaotically near the singularity. Any matter falling in would experience intense tidal forces rapidly changing in direction, all while being compressed into an increasingly small volume. Physicists termed these oscillations Mixmaster dynamics, after a brand of mixer that was popular at the time that Belinskii, Khalatnikov, and Lifshitz made their discovery, because they have a similar effect on matter near a singularity as an electric mixer would have on dough.[249][191][250]

In the case of a charged (Reissner–Nordström) or rotating (Kerr) black hole, it is possible to avoid the singularity. Extending these solutions as far as possible reveals the hypothetical possibility of exiting the black hole into a different spacetime with the black hole acting as a wormhole.[136]: 257 The possibility of travelling to another universe is, however, only theoretical, since any perturbation would destroy this possibility.[251] It also appears to be possible to follow closed timelike curves (returning to one's own past) around the Kerr singularity, which leads to problems with causality like the grandfather paradox.[136]: 266 [252] However, processes inside the black hole, such as quantum gravity effects or mass inflation, might prevent closed timelike curves from arising.[252]

To solve technical issues with general relativity, some models of gravity do not include black hole singularities. These theoretical black holes without singularities are called regular, or nonsingular, black holes.[253][254] For example, the fuzzball model, based on string theory, states that black holes are actually made up of quantum microstates and need not have a singularity or an event horizon.[255][256] The theory of loop quantum gravity proposes that the curvature and density at the center of a black hole is large, but not infinite.[257]

Formation

[edit]Black holes are formed by gravitational collapse of massive stars, either by direct collapse or during a supernova explosion in a process called fallback.[258] Black holes can result from the merger of two neutron stars or a neutron star and a black hole.[259] Other more speculative mechanisms include primordial black holes created from density fluctuations in the early universe, the collapse of dark stars, a hypothetical object powered by annihilation of dark matter, or from hypothetical self-interacting dark matter.[260]

Supernova

[edit] Gas cloud being ripped apart by black hole at the centre of the Milky Way (observations from 2006, 2010 and 2013 are shown in blue, green and red, respectively)[261]

Gas cloud being ripped apart by black hole at the centre of the Milky Way (observations from 2006, 2010 and 2013 are shown in blue, green and red, respectively)[261]

Gravitational collapse occurs when an object's internal pressure is insufficient to resist the object's own gravity. At the end of a star's life, it will run out of hydrogen to fuse, and will start fusing more and more massive elements, until it gets to iron. Since the fusion of elements heavier than iron would require more energy than it would release, nuclear fusion ceases. If the iron core of the star is too massive, the star will no longer be able to support itself and will undergo gravitational collapse.[262][263]

While most of the energy released during gravitational collapse is emitted very quickly, an outside observer does not actually see the end of this process. Even though the collapse takes a finite amount of time from the reference frame of infalling matter, a distant observer would see the infalling material slow and halt just above the event horizon, due to gravitational time dilation. Light from the collapsing material takes longer and longer to reach the observer, with the delay growing to infinity as the emitting material reaches the event horizon. Thus the external observer never sees the formation of the event horizon; instead, the collapsing material seems to become dimmer and increasingly red-shifted, eventually fading away.[264]

Other mechanisms

[edit]Observations of quasars at redshift , less than a billion years after the Big Bang,[265][266] has led to investigations of other ways to form black holes. The accretion process to build supermassive black holes has a limiting rate of mass accumulation and a billion years is not enough time to reach quasar status. One suggestion is direct collapse of nearly pure hydrogen gas (low metalicity) clouds characteristic of the young universe, forming a supermassive star which collapses into a black hole. It has been suggested that seed black holes with typical masses of ~105 M☉ could have formed in this way which then could grow to ~109 M☉. However, the very large amount of gas required for direct collapse is not typically stable to fragmentation to form multiple stars. Thus another approach suggests massive star formation followed by collisions that seed massive black holes which ultimately merge to create a quasar.[267]: 85

A neutron star in a common envelope with a regular star can accrete sufficient material to collapse to a black hole or two neutron stars can merge. These avenues for the formation ob black holes are considered relatively rare.[268]

Primordial black holes and the Big Bang

[edit]In the current epoch of the universe, conditions needed to form black holes are rare and are mostly only found in stars. However, in the early universe, conditions may have allowed for black hole formations via other means. Fluctuations of spacetime soon after the Big Bang may have formed areas that were denser then their surroundings. Initially, these regions would not have been compact enough to form a black hole, but eventually, the curvature of spacetime in the regions become large enough to cause them to collapse into a black hole.[269][270] Different models for the early universe vary widely in their predictions of the scale of these fluctuations. Various models predict the creation of primordial black holes ranging from a Planck mass (~2.2×10−8 kg) to hundreds of thousands of solar masses.[271][272] Primordial black holes with masses less than 1015 g would have evaporated by now due to Hawking radiation.[131]

Despite the early universe being extremely dense, it did not re-collapse into a black hole during the Big Bang, since the universe was expanding rapidly and did not have the gravitational differential necessary for black hole formation. Models for the gravitational collapse of objects of relatively constant size, such as stars, do not necessarily apply in the same way to rapidly expanding space such as the Big Bang.[273][274][275]

High-energy collisions

[edit]In principle, black holes could be formed in high-energy particle collisions that achieve sufficient density, although no such events have been detected.[276][277] These hypothetical micro black holes, which could form from the collision of cosmic rays and Earth's atmosphere or in particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider, would not be able to aggregate additional mass.[278] Instead, they would evaporate in about 10−25 seconds, posing no threat to the Earth.[279]

Evolution

[edit]Merger

[edit]Black holes can also merge with other objects such as stars or even other black holes. This is thought to have been important, especially in the early growth of supermassive black holes, which could have formed from the aggregation of many smaller objects.[153] The process has also been proposed as the origin of some intermediate-mass black holes.[280][281] Mergers of supermassive black holes may take a long time: As a binary of supermassive black holes approach each other, most nearby stars are ejected, leaving little for the remaining black holes to gravitationally interact with that would allow them to get closer to each other. This phenomenon has been called the final parsec problem, as the distance at which this happens is usually around one parsec.[282][283]

Accretion of matter

[edit] The active galactic nucleus of galaxy Centaurus A in X-ray light, believed to be powered by a supermassive black hole (centre) and surrounded by x-ray binaries (blue dots).

The active galactic nucleus of galaxy Centaurus A in X-ray light, believed to be powered by a supermassive black hole (centre) and surrounded by x-ray binaries (blue dots).

An artist's impression (top) of a supermassive black hole tidally deforming a star based on observations from the Chandra X-ray observatory and the European Southern Observatory.

An artist's impression (top) of a supermassive black hole tidally deforming a star based on observations from the Chandra X-ray observatory and the European Southern Observatory.

When a black hole accretes matter, the gas in the inner accretion disk orbits at very high speeds because of its proximity to the black hole. The resulting friction heats the inner disk to temperatures at which it emits vast amounts of electromagnetic radiation (mainly X-rays) detectable by telescopes. By the time the matter of the disk reaches the ISCO, between 5.7% and 42% of its mass will have been converted to energy, depending on the black hole's spin. About 90% of this energy is released within about 20 black hole radii.[176] In many cases, accretion disks are accompanied by relativistic jets that are emitted along the black hole's poles, which carry away much of the energy. The mechanism for the creation of these jets is currently not well understood, in part due to insufficient data.[284]

Many of the universe's most energetic phenomena have been attributed to the accretion of matter on black holes. Active galactic nuclei and quasars are believed to be the accretion disks of supermassive black holes.[285] X-ray binaries are generally accepted to be binary star systems in which one of the two stars is a compact object accreting matter from its companion.[285] Ultraluminous X-ray sources may be the accretion disks of intermediate-mass black holes.[286]

At a certain rate of accretion, the outward radiation pressure will become as strong as the inward gravitational force, and the black hole should unable to accrete any faster. This limit is called the Eddington limit. However, many black holes accrete beyond this rate due to their non-spherical geometry or instabilities in the accretion disk. Accretion beyond the limit is called Super-Eddington accretion and may have been commonplace in the early universe.[287][288]

Stars have been observed to get torn apart by tidal forces in the immediate vicinity of supermassive black holes in galaxy nuclei, in what is known as a tidal disruption event (TDE). Some of the material from the disrupted star forms an accretion disk around the black hole, which emits observable electromagnetic radiation.[289][290]

Interaction with galaxies

[edit]The correlation between the masses of supermassive black holes in the centres of galaxies with the velocity dispersion and mass of stars in their host bulges suggests that the formation of galaxies and the formation of their central black holes are related. Black hole winds from rapid accretion, particularly when the galaxy itself is still accreting matter, can compress gas nearby, accelerating star formation. However, if the winds become too strong, the black hole may blow nearly all of the gas out of the galaxy, quenching star formation. Black hole jets may also energize nearby cavities of plasma and eject low-entropy gas from out of the galactic core, causing gas in galactic centers to be hotter than expected.[291]

Evaporation

[edit]In 1974, Stephen Hawking predicted that black holes emit small amounts of thermal radiation at a temperature of , where is the reduced Planck constant, is the speed of light, is the gravitational constant, is the mass of the black hole and is the Boltzmann constant.[53] This effect has become known as Hawking radiation. By applying quantum field theory to black holes, Hawking determined that a black hole should continuously emit thermal blackbody radiation. This theory was supported by previous work by Jacob Bekenstein, who theorized that black holes should have a finite entropy proportional to their surface area, and therefore should also have a temperature.[292]

Since Hawking's publication, many others have mathematically verified the result through different approaches.[292] If Hawking's theory of black hole radiation is correct, then black holes are expected to shrink and evaporate over time as they lose mass by the emission of photons and other particles.[53] The temperature of this thermal spectrum (Hawking temperature) is proportional to the surface gravity of the black hole, which is inversely proportional to the mass. Hence, large black holes emit less radiation than small black holes.[293]: Ch. 9.6 [294] A stellar black hole of 1 M☉ has a Hawking temperature of 62 nanokelvins.[295] This is far less than the 2.7 K temperature of the cosmic microwave background radiation. Stellar-mass or larger black holes receive more mass from the cosmic microwave background than they emit through Hawking radiation and thus will grow instead of shrinking.[296] To have a Hawking temperature larger than 2.7 K (and be able to evaporate), a black hole would need a mass less than the Moon. Such a black hole would have a diameter of less than a tenth of a millimetre.[297]

The Hawking radiation for an astrophysical black hole is predicted to be very weak and would thus be exceedingly difficult to detect from Earth. A possible exception is the burst of gamma rays emitted in the last stage of the evaporation of primordial black holes. Searches for such flashes have proven unsuccessful and provide stringent limits on the possibility of existence of low mass primordial black holes, with modern research predicting that primordial black holes must make up less than a fraction of 10−7 of the universe's total mass.[298][131] NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, launched in 2008, has searched for these flashes, but has not yet found any.[299][300]

Laws of mechanics and thermodynamics

[edit] A black hole's entropy scales with the surface area of its event horizon.

A black hole's entropy scales with the surface area of its event horizon.

The properties of a black hole are constrained and interrelated by the theories that predict these properties. When based on general relativity, these relationships are called the laws of black hole mechanics. For a black hole that is not still forming or accreting matter, the zeroth law of black hole mechanics states the black hole's surface gravity is constant across the event horizon. The first law relates changes in the black hole's surface area, angular momentum, and charge to changes in its energy. The second law says the surface area of a black hole never decreases on its own. Finally, the third law says that the surface gravity of a black hole is never zero. These laws are mathematical analogs of the laws of thermodynamics. They are not equivalent, however, because, according to general relativity without quantum mechanics, a black hole can never emit radiation, and thus its temperature must always be zero.[301]: 11 [302]

Quantum mechanics predicts that a black hole will continuously emit thermal Hawking radiation, and therefore must always have a nonzero temperature. It also predicts that all black holes have entropy which scales with their surface area. When quantum mechanics is accounted for, the laws of black hole mechanics become equivalent to the classical laws of thermodynamics.[301][303] However, these conclusions are derived without a complete theory of quantum gravity, although many potential theories do predict black holes having entropy and temperature. Thus, the true quantum nature of black hole thermodynamics continues to be debated.[301]: 29 [302]

Observational evidence

[edit]Millions of black holes with around 30 solar masses derived from stellar collapse are expected to exist in the Milky Way. Even a dwarf galaxy like Draco should have hundreds.[304] Only a few of these have been detected. By nature, black holes do not themselves emit any electromagnetic radiation other than the hypothetical Hawking radiation, so astrophysicists searching for black holes must generally rely on indirect observations. The defining characteristic of a black hole is its event horizon. The horizon itself cannot be imaged[305] so all other possible explanations for these indirect observations must be considered and eliminated before concluding that a black hole has been observed.[306]: 11

Direct interferometry

[edit] As the Earth rotates, EHT telescopes observe from different angles.

As the Earth rotates, EHT telescopes observe from different angles.

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) is a global system of radio telescopes capable of directly observing a black hole shadow.[79] The angular resolution of a telescope is based on its aperture and the wavelengths it is observing. Because the angular diameters of Sagittarius A* and Messier 87* in the sky are very small, a single telescope would need to be about the size of the Earth to clearly distinguish their horizons using radio wavelengths. By combining data from several different radio telescopes around the world, the Event Horizon Telescope creates an effective aperture the diameter size of the Earth. The EHT team used imaging algorithms to compute the most probable image from the data in its observations of Sagittarius A* and M87*.[307][308]

In April 2019, the EHT team debuted the first image of the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy M87.[309][310] The black hole's shadow appears as a dark circle in the centre of the image, bordered by the orange-red ring of its accretion disk.[311] The bottom half of the disk is brighter than the top due to Doppler beaming: Material at the bottom of the disk, which is travelling towards the viewer at relativistic speeds, appears brighter than the material at the top of the disk, which is travelling away from the viewer.[312][311] In April 2023, the EHT team presented an image of the shadow of the Messier 87 black hole and its high-energy jet, viewed together for the first time.[313][314]

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way

On 12 May 2022, the EHT released the first image of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way galaxy. The EHT team had previously detected magnetic field lines around the black hole, confirming theoretical predictions of magnetic fields around black holes.[315][316] Like M87*, Sagittarius A*'s shadow and accretion disk can be seen in the EHT image, with the size of the shadow matching theoretical projections.[310][317] Although the image of Sagittarius A* was created through the same process as for M87*, it was significantly more complex to image Sagittarius A* because of the instability of its surroundings. Because Sagittarius A* is one thousand times less massive as M87*, its accretion disk has a much shorter orbital period, so the environment around Sagittarius A* was rapidly changing as the EHT team was trying to image it.[318] Additionally, turbulent plasma lies between Sagittarius A* and Earth, preventing resolution of the image at longer wavelengths.[319]

Detection of gravitational waves from merging black holes

[edit] LIGO measurement of the gravitational waves at the Livingston (right) and Hanford (left) detectors, compared with the theoretical predicted values

LIGO measurement of the gravitational waves at the Livingston (right) and Hanford (left) detectors, compared with the theoretical predicted values

Gravitational-wave interferometry can be used to detect merging black holes and other compact objects. In this method, a laser beam is split down two long arms of a tunnel. The laser beams reflect off of mirrors in the tunnels and converge at the intersection of the arms, cancelling each other out. However, when a gravitational wave passes, it warps spacetime, changing the lengths of the arms themselves. Since each laser beam is now travelling a slightly different distance, they do not cancel out and produce a recognizable signal. Analysis of the signal can give scientists information about what caused the gravitational waves. Since gravitational waves are very weak, gravitational-wave observatories such as LIGO must have arms several kilometers long and carefully control for noise from Earth to be able to detect these gravitational waves.[320]

On 14 September 2015, the LIGO gravitational wave observatory made the first-ever successful direct observation of gravitational waves.[73][321] The signal was consistent with theoretical predictions for the gravitational waves produced by the merger of two black holes: one with about 36 solar masses, and the other around 29 solar masses.[73][322] The signal observed by LIGO also included the start of the post-merger ringdown, the signal produced as the newly formed compact object settles down to a stationary state.[323] From the ringdown, the LIGO team was able to determine that the resulting merged black hole was spinning at 67% of the maximum rate and had a mass of 62 solar masses, having lost three solar masses as gravitational waves during the merger.[73][322]

The observation also provides the first observational evidence for the existence of stellar-mass black hole binaries. Furthermore, it is the first observational evidence of stellar-mass black holes weighing 25 solar masses or more.[324]

Since then, many more gravitational wave events have been observed.[325]

Stars orbiting Sagittarius A*

[edit]The proper motions of stars near the centre of the Milky Way provide strong observational evidence that these stars are orbiting a supermassive black hole.[326] Since 1995, astronomers have tracked the motions of 90 stars orbiting an invisible object coincident with the radio source Sagittarius A*. In 1998, by fitting the motions of the stars to Keplerian orbits, the astronomers were able to infer that Sagittarius A* must be a 2.6×106 M☉ object must be contained within a radius of 0.02 light-years.[327]

Since then, one of the stars—called S2—has completed a full orbit. From the orbital data, astronomers were able to refine the calculations of the mass of Sagittarius A* to 4.3×106 M☉, with a radius of less than 0.002 light-years.[326] This upper limit radius is larger than the Schwarzschild radius for the estimated mass, so the combination does not prove Sagittarius A* is a black hole. Nevertheless, these observations strongly suggest that the central object is a supermassive black hole as there are no other plausible scenarios for confining so much invisible mass into such a small volume.[327] Additionally, there is some observational evidence that this object might possess an event horizon, a feature unique to black holes.[328] The Event Horizon Telescope image of Sagittarius A*, released in 2022, provided further confirmation that it is indeed a black hole.[329]

Binaries

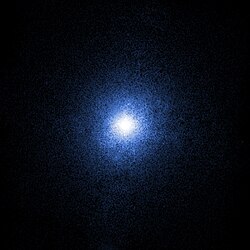

[edit] A Chandra X-Ray Observatory image of Cygnus X-1, which was the first strong black hole candidate discovered

A Chandra X-Ray Observatory image of Cygnus X-1, which was the first strong black hole candidate discovered

X-ray binaries are binary systems that emit a majority of their radiation in the X-ray part of the electromagnetic spectrum. These X-ray emissions result when a compact object accretes matter from an ordinary star.[330] The presence of an ordinary star in such a system provides an opportunity for studying the central object and to determine if it might be a black hole. By measuring the orbital period of the binary, the distance to the binary from Earth, and the mass of the companion star, scientists can estimate the mass of the compact object.[331] The Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit (TOV limit) dictates the largest mass a nonrotating neutron star can be, and is estimated to be about two solar masses. While a rotating neutron star can be slightly more massive, if the compact object is much more massive than the TOV limit, it cannot be a neutron star and is generally expected to be a black hole.[285][332]

The first strong candidate for a black hole, Cygnus X-1, was discovered in this way by Charles Thomas Bolton,[9] Louise Webster, and Paul Murdin[8] in 1972.[333][51] Observations of rotation broadening of the optical star reported in 1986 lead to a compact object mass estimate of 16 solar masses, with 7 solar masses as the lower bound.[285] In 2011, this estimate was updated to 14.1±1.0 M☉ for the black hole and 19.2±1.9 M☉ for the optical stellar companion.[334]

X-ray binaries can be categorized as either low-mass or high-mass; This classification is based on the mass of the companion star, not the compact object itself.[137] In a class of X-ray binaries called soft X-ray transients, the companion star is of relatively low mass, allowing for more accurate estimates of the black hole mass. These systems actively emit X-rays for only several months once every 10–50 years. During the period of low X-ray emission, called quiescence, the accretion disk is extremely faint, allowing detailed observation of the companion star.[285] Numerous black hole candidates have been measured by this method.[335] Black holes are also sometimes found in binaries with other compact objects, such as white dwarfs,[137] neutron stars,[336][337] and other black holes.[338][339]

Galactic nuclei

[edit]The centre of nearly every galaxy contains a supermassive black hole.[340] The close observational correlation between the mass of this hole and the velocity dispersion of the host galaxy's bulge, known as the M–sigma relation, strongly suggests a connection between the formation of the black hole and that of the galaxy itself.[341][342]

Active galactic nucleus

[edit] Detection of unusually bright X-ray flare from Sagittarius A*, a black hole in the centre of the Milky Way galaxy on 5 January 2015[343]

Detection of unusually bright X-ray flare from Sagittarius A*, a black hole in the centre of the Milky Way galaxy on 5 January 2015[343]

Astronomers use the term active galaxy to describe galaxies with unusual characteristics, such as unusual spectral line emission and very strong radio emission. Theoretical and observational studies have shown that the high levels of activity in the centers of these galaxies, regions called active galactic nuclei (AGN), may be explained by accretion onto supermassive black holes. These AGN consist of a central black hole that may be millions or billions of times more massive than the Sun, a disk of interstellar gas and dust called an accretion disk, and two jets perpendicular to the accretion disk.[344][345][346]

Although supermassive black holes are expected to be found in most AGN, only some galaxies' nuclei have been more carefully studied in attempts to both identify and measure the actual masses of the central supermassive black hole candidates. Some of the most notable galaxies with supermassive black hole candidates include the Andromeda Galaxy, Messier 32, Messier 87, the Sombrero Galaxy, and the Milky Way itself.[347][348]

Quasi-periodic oscillations

[edit]The X-ray emissions from the disks of accreting black holes sometimes flicker at certain frequencies. These signals are called quasi-periodic oscillations and are thought to be caused by material moving along the inner edge of the accretion disk (the innermost stable circular orbit).[349][350] Some scientists also suggest that these oscillations may be caused by the black hole's axis of rotation being out of alignment with the binary system's axis of rotation.[350] Since the frequency of quasi-periodic oscillations is correlated with the mass and rotation rate of the compact object, it can be used as an alternative way to determine the properties of candidate black holes.[349][350][351]

Microlensing

[edit] The intense gravitational field of a foreground black hole acts like a powerful lens, distorting and brightening the image of a background star.

The intense gravitational field of a foreground black hole acts like a powerful lens, distorting and brightening the image of a background star.