| |

| Author | Anne Carson |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Romance |

| Publisher | Alfred A. Knopf |

Publication date | March 31, 1998 |

| Publication place | Canada |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 149 pp |

| Awards |

|

| ISBN | 0-375-40133-4 |

| OCLC | 37975550 |

| 811/.54 21 | |

| LC Class | PS3553.A7667 A94 1998 |

| Followed by | Red Doc> |

Autobiography of Red is a verse novel by Anne Carson, published in 1998 by Alfred A. Knopf.[1]

The work reimagines the plot of the fragmentary poem Geryoneis by the ancient Greek poet Stesichorus, which recounts the episode in the life of Heracles in which he kills the red, winged monster known as Geryon to steal his cattle. In the novel, Carson imagines Geryon as a gay teenager with wings living in the present day who falls in love with a rebellious young man named Heracles, who breaks his heart.[2][3][4]

The novel is considered one of Carson's best works and the one that brought her name to fame.[2][5] It is also regarded as one of the most complex characterizations of an LGBT character in contemporary English-language literature.[6] Among the main themes it addresses are lost love,[7] the image of the artist as a monstrous being, and the role of translations.[8]

In 2013, Carson published a sequel to the work titled Red Doc> in which she continues the story of Geryon and Heracles, employing a similar poetic style.[9]

Summary

[edit]Autobiography of Red is the story of a boy named Geryon who, at least in a metaphorical sense, is the Greek monster Geryon. It is unclear how much of the mythological Geryon's connection to the story's Geryon is literal, and how much is metaphorical.

Geryon is a small child (and at the same time a red, winged monster) who lives on an Atlantic island with his family. At a young age, his older brother begins to sexually abuse him, leading Geryon to start writing an autobiography. When he reaches 14, he meets a boy two years older named Heracles, with whom he falls deeply in love. Heracles and Geryon begin a romantic relationship and later travel to Hades,[10] Heracles' hometown, on the other side of the island. There they stay with Heracles' grandmother, who shows them a photograph of a volcano that erupted in 1923 and destroyed the town. Days later, Heracles ends the relationship with Geryon and sends him back home, leaving him devastated.[11]

When he reaches 22 years old,[12] Geryon travels to Buenos Aires, where he attends a philosophy conference and visits a tango bar. The next day he coincidentally runs into Heracles, who had come to Buenos Aires with Ancash, his new boyfriend, to record volcano sounds for a documentary about Emily Dickinson.[13] Geryon feels his old feelings for Heracles rekindle and becomes jealous of Ancash. Days later, the three meet, and after Heracles steals a wooden tiger from a carousel, they agree to travel together to Peru, Ancash's home country.[14] During the plane trip, Geryon rests his head on Heracles' shoulder, who discreetly begins to masturbate him while Ancash sleeps.[15]

Once they arrive in Lima, they spend the night with Ancash's mother, who was originally from Huaraz. Ancash discovers Geryon's wings and is surprised by them.[14] He then tells him the legend of the "Yazcol Yazcamac," men who were thrown into a volcano in a town called Jucu, north of Huaraz, and emerged with red skin and wings after leaving behind their weaknesses and mortality. The next day they decide to travel to Huaraz. One night during the journey, Geryon and Heracles have sex, but Geryon cries upon realizing Heracles is not the same one he loved in his adolescence. The next morning, Ancash hits Geryon and asks if he still loves Heracles, to which he replies that he loved the Heracles of the past. After Ancash asks to see him fly,[16] Geryon takes his recorder at dawn and flies to the Jucu volcano while recording its sounds. In the novel's final chapter, Geryon, Heracles, and Ancash walk the streets of Jucu and watch the volcano's fire.[14]

The book also contains Carson's very loose translation of the Geryoneis fragments, using many anachronisms and taking many liberties, and some discussion of both Stesichorus and the Geryon myth, including a fictional interview with "Stesichoros", a veiled reference to Gertrude Stein.

Main characters

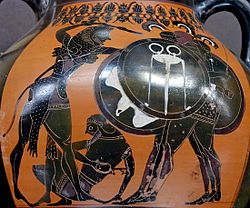

[edit] Heracles fighting Geryon. Attic amphora, c. 540 BC.

Heracles fighting Geryon. Attic amphora, c. 540 BC.

- Geryon: the story's protagonist, a gay teenager with wings, shy and melancholic in character.[2][3] From a young age he feels a propensity toward art, first by writing an autobiography in which he imagines his death similarly to the original Greek myth, later through photography.[17] When he meets Heracles he falls intensely in love with him. Unlike the literal murder in the Greek myth, the novel's Geryon experiences a metaphorical death when Heracles breaks his heart.[2][3] In the years following his romantic disappointment he lives depressed and finds escape in photography, until later reuniting with Heracles. To prevent people from seeing his wings he hides them under his jacket,[18] but later learns that red, winged people were those who survived volcano fires.[17]

- Heracles: a rebellious, burly, selfish, and charismatic young man,[2][6] two years older than Geryon and who describes himself as "someone who will never feel satisfied." They meet in chapter seven, when Heracles is sixteen and arrives on a bus from New Mexico. They soon become lovers and Heracles takes the more sexual and dominant role in the relationship. After a trip to his grandmother's house, Heracles ends things with Geryon and sends him home.[10] Years later they reunite in Buenos Aires, where Heracles had gone with his new boyfriend, Ancash.[17]

- Ancash: Heracles' new boyfriend, of Peruvian origin. He meets Geryon during his stay in Buenos Aires with Heracles; later the three decide to travel to Peru.[17] Ancash is the only character who speaks about Geryon's wings and upon discovering them reveals that Geryon belonged to a race of sacred men known as "Yazcol Yazcamac."[19] When he learns Geryon had sex with Heracles, he hits him, but they later talk and when Geryon admits he loved the Heracles of the past, Ancash says he wanted to see him use his wings.[20]

- Geryon's brother: mistreats Geryon from childhood, calls him stupid, and refuses to take him to his classroom at school. One night when Geryon stays in his room he sexually abuses him, a situation repeated for a long time in which his brother gives Geryon marbles as compensation. Years later he works as a sports commentator on radio.[21] In Greek mythological genealogy, as narrated in Hesiod's Theogony, Geryon has no brother but a sister, Echidna, mother of some of mythology's most famous monsters.[22]

Composition

[edit] Bust of the Greek poet Stesichorus, author of the Geryoneis.

Bust of the Greek poet Stesichorus, author of the Geryoneis.

The original idea for the work arose from Carson's interest in Geryon's story in Stesichorus' Geryoneis, particularly the character's monstrosity. Carson began translating the surviving fragments of the poem for pleasure but felt frustrated at not conveying what most attracted her to the story, both due to limitations of translating Greek to English and the lack of context created by the work's fragmentariness. This led her to rewrite the myth as a novel. Early versions were entirely in prose, but one day she experimented with form and tried alternating long and short lines, which she adopted for the final version.[23]

According to Carson, she decided to make Geryon and Heracles lovers due to her interest in how various homoerotic references are incorporated in classical Greek works, such as the Iliad.[23]

Structure and style

[edit]The work is divided into seven parts: two introductions, three appendices, the novel proper, and an epilogue.[10] The introductions are titled "Red Meat."[24] The first discusses the nature of adjectives and Stesichorus' inclination to focus on characters' interiority, a propensity Carson supports and which, according to her, distinguishes him from Homer's epic narratives.[25] The second introduction gathers surviving fragments of the Geryoneis, translated and ordered by the author. In the three appendices, Carson treats with a tone parodying academic discourse Stesichorus' blindness, supposedly caused by Helen of Troy, and the poet's attempts at atonement. The epilogue shows a fictional interview by Carson with Stesichorus.[10][26]

The novel section, titled "Autobiography of Red: A Romance,"[10] consists of about 13,000 lines divided into 47 chapters,[27] each one to seven pages long,[10] and narrates the story in third person chronologically.[28][29] Chapters have short titles, often single words, and are written in a lyric narrative style alternating long and short lines without rhymes. According to poet Elizabeth Macklin, the lines give the text supplementary punctuation and help generate emphasis.[10]

Six of the last seven chapters include the word "Photographs" in their title and describe photos included in Geryon's autobiography. The exception is the final chapter, titled "The Flashes in Which a Man Owns Himself."[30]

Critic Sam Anderson describes the book as follows:[31]

The book is subtitled "A Novel in Verse," but—as usual with Carson—neither "novel" nor "verse" quite seems to apply. It begins as if it were a critical study of the ancient Greek poet Stesichoros, with special emphasis on a few surviving fragments he wrote about a minor character from Greek mythology, Geryon, a winged red monster who lives on a red island herding red cattle. Geryon is most famous as a footnote in the life of Herakles, whose 10th labor was to sail to that island and steal those cattle—in the process of which, almost as an afterthought, he killed Geryon by shooting him in the head with an arrow.

Autobiography of Red purports to be Geryon's autobiography. Carson transposes Geryon's story, however, into the modern world, so that he is suddenly not just a monster but a moody, artsy, gay teenage boy navigating the difficulties of sex and love and identity. His chief tormentor is Herakles, a charismatic ne'er-do-well who ends up breaking Geryon's heart. The book is strange and sweet and funny, and the remoteness of the ancient myth crossed with the familiarity of the modern setting (hockey practice, buses, baby sitters) creates a particularly Carsonian effect: the paradox of distant closeness.

Central themes

[edit]Geryon's monstrosity

[edit] Drawing of Geryon by William Blake (1824), based on Dante's description in the Divine Comedy.

Drawing of Geryon by William Blake (1824), based on Dante's description in the Divine Comedy.

Autobiography of Red is a coming-of-age novel exploring Geryon's childhood and youth, described as a red monster with wings, and his emotions upon being rejected by others due to his monstrous characteristics.[32] Carson's humanization of Geryon fits a trend in recent centuries' literature seeking to revalue the "monster" beyond its traditional role as heroic figure obstacle. Geryon's case is notable because Stesichorus himself had already made an initial effort to humanize his figure by narrating events from his perspective in the Geryoneis. Geryon's ambivalent representation is why figures like Dante Alighieri showed him as the "personification of fraud," with a body mixing human and animal parts.[33]

In the novel, Carson goes further than Stesichorus and completely reverses protagonist and antagonist roles of Heracles and Geryon by showing the latter as a victim of violence despite his monster identity.[34]

One of the protagonist's first revealed characteristics states: "Geryon was a monster everything about him was red." Red's importance lies in its metaphor for Geryon's monstrosity, the main characteristic leading to rejection. The exact meaning of red has been explored by several scholars. Interpretations of what it symbolizes in Geryon include: his interiority,[29] his creativity and inner strength.[35][17] According to professor Dina Georgis, Geryon's wings represent the physical mark of everything making him feel vulnerable and different from others,[36] particularly his homosexuality.[1] This is reflected in the work in his attempts to hide his wings from others, fearing their presence would arouse hatred and rejection.[37]

An important point is that, despite Geryon's wings and red color not being mentioned by any other character throughout most of the book, their presence is literal and not metaphorical. Although lack of mentions could be explained by Geryon's attempts to hide his wings under jackets, it is peculiar that not even Heracles mentions them in moments when their presence would be obvious, like during sex. However, the wings later provoke a quite realistic reaction when seen by Ancash, Heracles' new boyfriend. Moreover, near the novel's end, Geryon uses his wings once to fly.[38]

Returning to Geryon, Carson is explicit in narrating how his monstrous characteristics, instead of signaling danger, are marks leading to exclusion.[39] From childhood, Geryon feels marginalized by schoolmates and mistreated by his brother, leading him to isolate himself. When his brother begins sexually abusing him, one tactic to keep silent is threatening to tell at home how "nobody [likes him] at school."[40]

Geryon's constant self-questioning later leads him to ask: "Who can blame a monster for being red?" as rejection of the classical monster role narrative that Geryon refuses to embody. At the novel's end, Geryon finally frees himself from the bonds imposed by his monstrosity without rejecting this part of his identity but accepting it as integral to himself, without shame or guilt. Once discovering his relation to the "Yazcol Yazcamac," Geryon flies into a volcano crater and emerges as a heroic figure, still with characteristics defining him as monster but having left insecurities behind.[41]

Art as means of survival

[edit]Considering abuses Geryon suffers as a child and pain from breakup with Heracles, the novel can also be interpreted as a survival story from trauma through art.[42] From a young age, Geryon navigates an environment where unequal power relations intertwine with sexual desire. This occurs in his relationship with Heracles but much earlier with his older brother, who mistreats him from the work's start and exerts the dominant role in interactions. This later becomes sexual abuse Geryon suffers from his brother, based on a "sex economy" in exchange for marbles. The power position difference is exemplified when his brother asks about his favorite weapon, to which Geryon replies a cage. The response is ridiculed by his brother, as from his dominant position every weapon must fulfill an active role and he could not conceive that for Geryon the best weapon was something to protect himself.[43]

Sexual abuse also leads Geryon to see his own interiority as the only refuge distancing him from his brother's abuses. This escape seeking safety manifests through writing his autobiography, where he decides to write "all interior things" and "omit all exterior things." He also tries expressing himself through a sculpture of himself attaching a cigarette and ten-dollar bill to a tomato, markedly red object lacking agency. According to professor Geordie Miller, this bill represents Geryon's attempt to communicate abuse to his mother, as the day after his brother first raped him he gave him a one-dollar bill as compensation.[44][45]

When his teacher forces him to change his autobiography's tragic ending, Geryon imagines a world where "beautiful red breezes blew hand to hand." This image represents the idea of a liberated Geryon who could move through the world without his individuality generating rejection.[46] According to Miller, the demand to change his text by an authority figure echoes Stesichorus' own palinode supposedly written to silence Helen of Troy's wrath.[47]

Geryon's artistic evolution later takes a new direction. When language becomes insufficient to express his experience, he decides to start taking photos. Geryon's fascination with photography arises when Heracles' grandmother shows him a photo titled "Red Patience," showing a volcano eruption captured with a fifteen-minute exposure. By the time Heracles ends the relationship, the autobiography he had been writing since childhood had transformed into a "photographic essay."[48] Through photography, Geryon attempts to capture fragments of his own identity that could not be expressed in written entries of his autobiography.[49] An example is the photograph titled "Jealous of My Little Sensations," showing a red rabbit tied with a white ribbon while laughing. According to professor Rachel Mindell, the emotion expressed in the photo arises from vulnerability felt in his relationship with Heracles, about to end, plus Geryon's own view of himself, expressed in a tied animal. Depression from separation is later expressed in another photograph, titled "If He Sleeps He Will Do Well."[50]

Relationship with Heracles and romantic breakup

[edit] Hercules Defeats King Geryon, oil on canvas by Francisco de Zurbarán (1634).

Hercules Defeats King Geryon, oil on canvas by Francisco de Zurbarán (1634).

Other central themes in Autobiography of Red are erotic desire, romantic love, and pain from abandonment in a breakup. These have been obsessions throughout Carson's literary career, with interest in romantic relationships present since her work Eros the Bittersweet (1986), where she discusses Greek romantic poetry based on her doctoral thesis in classics. The shift toward exploring pain after a breakup occurred in 1995 in her poems The Anthropology of Water and Glass Essay, which can be considered direct predecessors of Autobiography of Red. In The Anthropology of Water, besides the theme of romantic separation, other similarities with the work are: similar style, language use, and even incorporation of a sequence of photographs.[51]

The moment Geryon meets Heracles is described with great poetic intensity to mark the impact on the protagonist's life. "They were two superior eels at the bottom of the tank and they recognized each other like italic letters," Carson writes about Geryon's falling in love. The event also marks a break in family interactions, as the role his mother previously had in his life passes entirely to Heracles, a dynamic narrated in a chapter appropriately titled "Change." Overall, love leads Geryon to isolate more and surrender completely to the relationship.[52]

Heracles, for his part, appears as an active and uncomplicated young man only seeking fun and pleasure. In this sense he has similarities with Geryon's brother and his relationship could be understood as a transfer of that old subjugation dynamic.[53] Heracles even describes himself once as "tamer of monsters," referring to Geryon.[54] Another aspect of the relationship is that Heracles never reciprocates the same love level Geryon feels for him and several times admonishes him for his sensitivity. "I hate when you cry... Can't you just fuck and not think?" he complains one night.[53] On a more fundamental level, Heracles and Geryon conceive two distinct ways of understanding a relationship. While Geryon seeks to be dominated and persuaded, Heracles sees love as an adventure to conquer.[55]

Heracles' inability to understand Geryon's perspective is expressed in his failure to see him as he is, as from the novel's beginning red has represented Geryon's interiority, yet Heracles imagines Geryon as yellow in his dreams.[53] However, Heracles is not the only one deceiving himself, as even when it becomes clear their relationship is about to end, Geryon refuses to accept it. This is reflected in a conversation where Heracles notes stars seen in the sky are already dead and what he sees are only "memories." However, Geryon refuses to acknowledge it and prefers living in the memory of their love rather than accepting separation.[56]

When ending the relationship with Geryon, Heracles states he does so because they are "true friends" and thus wants "to see him free," to which Geryon mentally replies "I don't want to be free I want to be with you," rejecting Heracles' attitude of refusing to recognize his pain.[57] Beyond that, Geryon's rejection of seeking freedom and preference to see himself as confined receive several references in the novel as part of his characterization during childhood and adolescence. Besides the "cage" reference when his brother asks about his favorite weapon and the photo of the red rabbit tied with a white ribbon, several descriptions of his emotional state speak of feeling "packed in himself" or like a "locked box."[49] Heracles himself tells him once, before they had broken up, that it depressed him that all his drawings were about captivity, after Geryon wrote graffiti saying "SLAVEOFLOVE."[58]

Heracles' abandonment leaves Geryon devastated for years and plunges him into mourning for his lost love from which he does not try to escape,[59] but seeks escape in his interiority while pain continues consuming him.[57] Photography again becomes the method to express his emotions, this time through a fifteen-minute exposure of a fly drowning in a rain bucket titled "If He Sleeps He Will Do Well." The fly choice is important because shortly before Geryon had described himself as "as weak as a fly."[12] However, despite the pain he feels, separation gives Geryon opportunity to feel at peace and later finds in his autobiography a reason to continue.[60]

Years later, when reuniting with Heracles in Buenos Aires, Geryon feels his desire for him awaken. However, when they later have sex, Geryon begins crying while imagining telling him: "Long ago I loved you, now I no longer know who you are" and meditates on how two people can be together yet feel separated. Geryon's realization is that he finally understands the love he felt could not survive indefinitely nor prevent Heracles from ceasing to represent the adolescent idealization existing in his mind. On a profound level, Geryon understands he and Heracles were never compatible nor could have formed the union Geryon dreamed of.[61] When Ancash confronts Geryon for having sex with Heracles and asks if he still loves him, Geryon reinforces this realization by confessing "In my dreams I love him (...) dreams of past days." This allows Geryon to finally leave Heracles behind.[16]

Volcano as catalyst for maturity

[edit] View of the city of Huaraz and the Cordillera Blanca, in Peru.

View of the city of Huaraz and the Cordillera Blanca, in Peru.

Throughout the novel, Geryon undertakes a character evolution process allowing him to find himself and assimilate life experiences. According to scholar Hsiao-chen Chien, this identity construction has a close relation to volcanoes' image in the text.[62] From his relationship time with Heracles, volcanoes hold strong symbolic charge as representation of Geryon's internal passions. Sexual desire birth is described as a "fire [that] twisted inside him," while after Heracles abandons him Geryon feels how "flames licked along the platforms of his interior" and "his heart and lungs turned to black crust."[63] The romantic breakup also represents a breaking point in his development and opens way for exploring his identity.[64]

Geryon's internal conflict is represented by his wings, discomforting him whenever he tries hiding them and he continues denying, as metaphor for his unresolved struggle to accept himself.[65] His wings represent freedom, but Geryon is not yet ready to use them.[66] Throughout the novel, Geryon constantly tries hiding his wings from others due to their symbol of his differences. The only time he lets them free is when alone, as when taking his first self-portrait, titled "No Tail!" showing him lying in bed in fetal position while deploying his wings in all majesty and text comparing them to a continent. However, the rest of the time Geryon prefers keeping his mythical greatness hidden from the world.[67]

When arriving in Peru, Geryon learns from Ancash that his red color and wings proved he was related to the "Yazcol Yazcamac," wise men descending into a volcano near Huaraz and returning cleansed of all weakness.[66] This revelation grants Geryon a new mythological identity and purpose, distinct from his subordinate character role in Heracles' story. In the novel's penultimate chapter, titled "Photographs: #1748," Geryon fulfills this role and flies into the legend's volcano,[68] marking the moment he reaches adult maturity and accepts characteristics making him unique.[69] This chapter's name references an Emily Dickinson poem precisely about a volcano ending with lines: "The only Secret People keep / Is Immortality." In the novel's end, Geryon, Ancash, and Heracles dress their faces with this "immortality,"[68] while Geryon silently meditates: "We are amazing beings, we are neighbors of fire."[66]

Reception

[edit]Autobiography of Red was warmly received by authors and critics, with highly positive reviews from Alice Munro, Michael Ondaatje, Susan Sontag, among others.[31] The book also sold unusually well for literary poetry, with at least 25,000 copies sold by the year 2000, two years after its publication.[70] It was described as "one of the crossover classics of contemporary poetry: poetry that can seduce even people who don't like poetry"[31] and Carson herself as "that rarest of rare things, a bestselling poet."[70]

The book was referenced, alongside Carson's previous work Eros the Bittersweet, in a 2004 episode of The L Word.[70]

The work received good critical reception and brought literary fame to Carson.[71][5] The review in British newspaper The Guardian, written by poet John Kinsella, acclaimed the work and described it as "one of the best volumes of poetry in English of the last decade." Among highlighted aspects was the intertextual confluence of myths, popular culture, comments on sexuality and theory, which Kinsella praised as "greatly achieved."[72] Jeffery Beam, in an Oyster Boy Review article, also applauded the novel and characterized it as "cinematic" and "Homeric in its originality." He particularly praised exploration of Geryon's romantic desires and references to classical texts.[18]

In an article published on Vulture website, American journalist Kathryn Schulz stated Autobiography of Red was a "very strange, very smart, intermittently funny, and ridiculously beautiful" work and focused on its coming-of-age novel character about Geryon's evolution from childhood to adulthood.[8] This aspect was also highlighted in the review of Spanish newspaper Infolibre, which also emphasized deconstruction of the original Greek myth.[73] Poet and professor Ruth Padel, in a review for The New York Times, referred to the work as a "profound love story" and highlighted the mix of witty and poetic tone, plus Carson's prose, which she called "sensual and funny, moving, musical and tender, brilliantly lit."[17] The work's style was also praised in the Kirkus Reviews review, characterizing it as innovative.[1]

Poet Mark Halliday, in the Chicago Review review, was more ambivalent. Among criticized aspects was the verse quality and work length, which he stated seemed "fanatically extended." He also floated the theory that Geryon was Carson's own alter ego, which, according to Halliday, would turn the character's homosexuality into a sort of cultural appropriation by Carson.[74] The Jacket magazine review was also unenthusiastic. Though calling the book's start promising and commending Carson's "concise lyricism," it stated narration became boring and its central theme of romantic rejection had been better addressed by Carson in previous works.[25]

Among recognitions received is the A. M. Klein Prize for Poetry from the Quebec Writers' Federation, won in its 1998 edition,[75] and a nomination for the National Book Critics Circle Award.[76] The novel has also been praised by authors like Ocean Vuong[77] and Mónica Ojeda, who called it her favorite literary work.[78]

Spanish translations

[edit]- Autobiografía de Rojo. Una novela en verso. Anne Carson. Translation by Tedi López Mills. Editorial Calamus. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura. First edition. Mexico, 2009. ISBN 978-607-7622-33-8

- Autobiografía de Rojo. Una novela en verso. Anne Carson. Translation by Jordi Doce. Editorial Pre-Textos. Valencia. 2016. ISBN 978-841-6453-46-7

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson". Kirkus Reviews. April 15, 1998. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Fried, Daisy (April 19, 2013). "Other Labyrinths. 'Red Doc,' by Anne Carson". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c Crown, Sarah (April 16, 2013). "Red Doc> by Anne Carson – review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013.

- ^ McGinty, Patrick (2013). "Living the past end of the myth: Anne Carson's Red Doc>". Propeller Magazine. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013.

- ^ a b "Fiction Book Review: Red Doc> by Anne Carson". Publishers Weekly. March 18, 2013. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Dean, Tacita (December 16, 2021). "Anne Carson Punches a Hole Through Greek Myth". Interview. Archived from the original on December 16, 2021.

- ^ Overby, Whitten (September 5, 2008). "Book Review: "Autobiography of Red" and "The Beauty of the Husband" by Anne Carson". The Wesleyan Argus. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Schulz, Kathryn (March 3, 2013). "Schulz on Anne Carson's Time-Traveling, Mind-Bending Red Doc>". Vulture. Archived from the original on March 9, 2013.

- ^ Baldwin, Rosecrans (March 6, 2013). "Monsters, Myths And Poetic License In Anne Carson's 'Red Doc'". NPR. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Macklin, Elizabeth (August 12, 2014). "Review: Autobiography of Red". Boston Review. Archived from the original on January 15, 2022.

- ^ Hall 2009, p. 14-16.

- ^ a b Mindell 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Hall 2009, p. 18-21.

- ^ a b c Carson, Anne (1999). Autobiography of Red: a novel in verse (1st Vintage Contemporaries ed., Aug. 1999 ed.). Vintage Contemporaries. ISBN 978-0-345-80701-4. OCLC 829300682.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 81-82.

- ^ a b Chien 2015, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f Padel, Ruth (May 3, 1998). "Seeing Red". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Beam, Jeffery (1998). "Autobiography of Red & Eros the Bittersweet, by Anne Carsons". Oyster Boy Review. Archived from the original on July 13, 2013.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 21-24.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 75-76.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 30-32, 50.

- ^ Carmel 2013, p. 21, 48.

- ^ a b Watchel, Eleanor (June 10, 2014). "An Interview with Anne Carson". Brick. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 9.

- ^ a b McKenzie, Geraldine (2000). "Geraldine McKenzie reviews Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red". Jacket. Archived from the original on November 19, 2002.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 9, 11.

- ^ Baldwin, Rosecrans (March 6, 2013). "Monsters, Myths And Poetic License In Anne Carson's 'Red Doc'". NPR. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 5.

- ^ a b Georgis 2014, p. 155.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Sam Anderson, "The Inscrutable Brilliance of Anne Carson," The New York Times Magazine, March 17, 2013.

- ^ Carmel 2013, p. 5.

- ^ Ng 2010, p. 1-3.

- ^ Ng 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Padel, Ruth (May 3, 1998). "Seeing Red". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2019.

- ^ Georgis 2014, p. 158.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 24.

- ^ Wahl 1999, p. 182-183.

- ^ Schenstead-Harris 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 32.

- ^ Ng 2010, p. 7-8.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 5, 161.

- ^ Miller 2011, p. 157-158.

- ^ Miller 2011, p. 158-159.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Talei 2016, p. 5-6.

- ^ Miller 2011, p. 159.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 14, 16-17.

- ^ a b Ducasse, Sébastien (June 15, 2007). "Metaphor as Self-Discovery in Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red: A Novel in Verse". E-rea. Revue électronique d’études sur le monde anglophone (5.1). doi:10.4000/erea.190. ISSN 1638-1718. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 17, 19.

- ^ Wahl 1999, p. 181, 185.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 36, 39.

- ^ a b c Georgis 2014, p. 162.

- ^ Miller 2011, p. 160.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 28.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 17.

- ^ a b Georgis 2014, p. 163.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 44.

- ^ Wahl 1999, p. 181.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 47-48.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 31.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 9, 11.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 13.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 26.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Talei 2016, p. 7-8.

- ^ Mindell 2015, p. 20.

- ^ a b Miller 2011, p. 164-165.

- ^ Chien 2015, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Liss, Sarah (March 11, 2003). "Myth Interpretation". The Walrus.

- ^ García, Beatriz (June 19, 2020). "Three books to get to know Anne Carson". Al Día News. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020.

- ^ Baldwin, Rosecrans (March 6, 2013). "Monsters, Myths And Poetic License In Anne Carson's 'Red Doc'". NPR. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022.

- ^ Palacios, Gema (2016-10-07). "'Autobiografía de Rojo', de Anne Carson". Infolibre (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2022-01-15.

- ^ Haliday, Mark (1999). "Autobiography of Red: A Novel in Verse". Chicago Review. 45 (2).

- ^ "1998 Awards Gala - Winners". Quebec Writers' Federation. 1998. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019.

- ^ Burt, Stephen (April 3, 2000). "Anne Carson: Poetry Without Borders". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on January 9, 2012.

- ^ Button, Liz (May 22, 2019). "A Q&A With Ocean Vuong, Author of June's #1 Indie Next List Pick". American Booksellers Association. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020.

- ^ Cabrera Junco, Jaime (December 3, 2020). "Mónica Ojeda: «Me interesa la parte sensorial de la literatura»". Leer por gusto. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mindell, Rachel (2015). What is a hole made of: Queen identity and grief in Autobiography of Red and Red Doc> (Thesis). University of Montana. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020.

- Georgis, Dina (2014). "Discarded Histories and Queer Affects in Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red". Studies in Gender and Sexuality. 15 (2): 154–166. doi:10.1080/15240657.2014.911054. ISSN 1524-0657.

- Miller, Geordie (2011). ""Shifting Ground": Breaking (from) Baudrillard's "Code" in Autobiography of Red". Canadian Literature (Autumn/Winter): 152–167.

- Wahl, Sharon (1999). Carson, Anne (ed.). "Erotic Sufferings: "Autobiography of Red" and Other Anthropologies". The Iowa Review. 29 (1): 180–188. ISSN 0021-065X.

- Chien, Hsiao-chen (2015). Coming-of-Im(age): In Quest of the Self in Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red (Thesis). National Sun Yat-sen University. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022.

- Hall, Edith (2009). The Autobiography of the Western Subject: Carson’s Geryon (PDF). Living Classics. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 22, 2022.

- Talei, Leila (2016). "The Claim of Fragmented Self in Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson". eTopia. doi:10.25071/1718-4657.36758. ISSN 1718-4657.

- Ng, Raphael (2010). "The Autobiography of a Modern Monster: Anne Carson's Geryon". inter-disciplinary.net.

- Schenstead-Harris, Leif (2012). The Monstrosity of Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red (PDF) (Thesis). Western University. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 24, 2022.

- Carmel, Joshua (2013). “Under the Seams Runs the Pain”: Four Greek Sources and Analogues for the Modern Monster in Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red (Thesis). Student Publications. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Tschofen, Monique (2004). ""First I Must Tell about Seeing": (De)monstrations of Visuality and the Dynamics of Metaphor in Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red". Canadian Literature (180): 31–50. ISSN 0008-4360.

- Lim, Huai-Ying Amanda (2006). The monstrous uncanny in Esta Spalding's Anchoress, Anne Caron's Autobiography of Red, and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (PDF) (Thesis). Archived from the original on August 15, 2017.

- Murray, Stuart (2005). "The Autobiographical Self: Phenomenology and the Limits of Narrative Self-Possession in Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red (Critical Essay)". English Studies in Canada (4).

External links

[edit] Media related to Autobiography of Red at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Autobiography of Red at Wikimedia Commons- New York Times Magazine on Anne Carson